INTRODUCTION

─────────────────────────────────

My first job after college was at the U.S. Naval

Research Laboratory, where I worked as a radio astronomer specializing in

Jupiter's radiation belts. Freed of time‑consuming college coursework, I was

able to broaden my reading. A few years earlier, the double‑helix structure of

DNA had been discovered. Perhaps stimulated by this, or maybe from the sheer

momentum of a childhood fascination with the way genes influence behavior, I

stumbled upon a thought which I now believe is the second‑most profound one of

the 20th Century: “outlaw genes.”

1963 Identification of Outlaw Genes

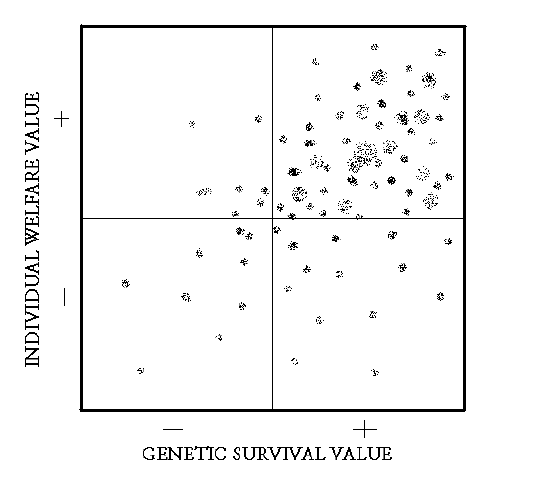

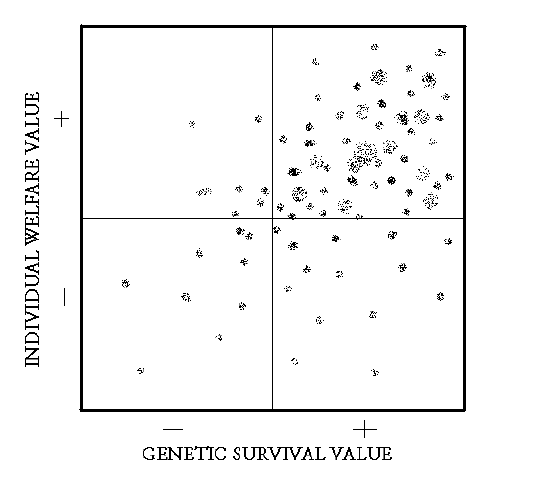

Figure I.01 An X‑Y matrix of "genetic

survival value" and "individual survival value" with

hypothetical markings of the locus of individual genes (as conceived in 1962).

In theory, any gene could be "placed"

in such a diagram (I hadn't encountered the concept of polygenes or pleiotropy

at that time, to be discussed in a later chapter). I imagined genes for this

and that, and placed them in the diagram. I recall thinking that there had to

be more dots in the upper‑right quadrant, corresponding to PGSV/PISV.

I realized that there shouldn't be many dots in

the opposite corner since NGSV/NISV mutations should quickly disappear.

Likewise, there shouldn't be many dots in the upper‑left NGSV/PISV quadrant, though

wouldn't it be nice if genes flourished when they promoted individual happiness

regardless of the cost to themselves. But it was the lower‑right corner that

awaited me with a surprise! Gene mutations of this type would "by

definition" flourish while "punishing" the individual carrying

them! And nothing could be done about it, short of replacing the forces of

natural selection with artificially created ones. This gene category has fascinated

me ever since!

Why hadn't I read about such genes? Surely

others knew about the inherent conflict between the individual and some of the

genes within! I looked forward to someday reading about these "outlaw

genes," and the philosophical dilemmas they posed. I stashed these

original diagrams and writings on the matter in a file, which remained closed

for decades. Nevertheless, I did not forget about these genes and during the

past four decades I have written about the subject in my spare time.

Coincidences

In the Fall of 1963 I enrolled at the

Although coincidences can shape lives, more

often they don't. While I was at

In this same year, 1963, William D. Hamilton

prepared manuscripts describing "inclusive fitness" (

I sometimes wonder how my life's path might have

differed if I had met Williams at

Overlooked Idea

Even now, four decades later, no one has written

clearly about the mischievous genes (to my knowledge). The Selfish Gene, by

Richard Dawkins (1976), comes close; but it never explicitly states that genes

"enslave" the individual for their selfish advancement while harming

the enslaved individual. Mean Genes (Burnham and Phelan,

2000) comes even closer, but its emphasis is on practical steps for resisting

self‑defeating behaviors rather than the theoretical origins of the genes

responsible for those behavioral predispositions.

Why is there such a paucity of discussion about

the philosophical implications of such a profound flaw in our origins and

present nature? Why have the professional anthropologists, philosophers and

others been so slow to address a subject that captured my unwavering attention

40 years ago, when I was fresh out of college and struggling to establish a

career in an unrelated field? Sociobiologists have written about conflicts

between competing gene alleles carried by individuals of various relatedness (

If

my idea has merit then sociobiologists have

simply overlooked an obvious “next step” in the unfolding of

implications for

the basic tenet of the field. The history of science has many examples

of

simple yet profound new ideas being overlooked by the professionals.

Every idea

has many discoverers, and probably most of them only half realize the

import of

their discovery. The oft‑discovered idea remains out of the public

domain until

it is grasped by someone having the energy to push it into the

mainstream while warding off attacks by established scientists

unthinkingly defending their academic turf.

Some of the genes within us are enemies of the

individual, in the same sense that outlaws are the enemies of a society. This

thought should challenge the thinking of every sentient being. The discipline

of philosophy should be resurrected, and restructured along sociobiological

precepts. If this is ever done the new field would have as its major

philosophical dilemma the following question:

"What should an individual do with the mental pull

toward behaviors that are harmful to individual welfare, yet which are present

because they favor the survival of the genes that create brain circuits

predisposing the individual to those behaviors?"

In other words, should the individual succumb to

instincts unthinkingly, given that the gene‑contrived emotional payoffs may

jeopardize individual safety and well‑being? Or, should the individual be wary

of instincts and thoughts that come easily and forfeit the emotional rewards

and ease of living in order to more surely live another day - to face the same

dilemma? Should some compromise be chosen?

How can any thinking person fail to be moved by these thoughts?

Overview of This Book

In writing this book I have wrestled with the

desire to proceed directly to the matters of outlaw genes, and how an

individual might deal with them. But every time I returned to the position that

a proper understanding of the individual's dilemma requires a large amount of

groundwork. For example, how can I celebrate the artisan way of life without

first describing why the genes created the artisan?

In the first edition of this book I included the

many groundwork chapters in their entirety before the culminating chapters. The

first person to read the book (Dr. M. J. Mahoney) stated that “Once I hit Levels

of Selection

[Chapter 12] I couldn't put the book down.” That’s when I

realized that I had violated the first principle of writing, which is

to

“quickly engage the reader before losing him.” Starting with the Second

Edition I shortened the groundwork chapters by moving most of that

material to

appendices. The groundwork chapters have become a primer for the

paradigm that

leads inevitably to the positions of the main message of this book.

The remainder of this introduction is a précis

for the book chapters.

There

is no guiding hand in evolution; the

natural process of the genes acting on their own behalf leads to

individuals

who are mere "agents" for these genes. This is the starting assumption

for "sociobiology," also called "evolutionary psychology," and

presented most effectively for the general public by Richard Dawkins in

The

Selfish Gene (1976). To understand the "blindness" of

evolution one must first understand that the universe is just a

"mechanism," that every phenomenon reduces to the action of blind

forces of physics acting upon dumb particles. This outlook is called

"reductionism," which is the subject of Chapter 1.

Lest the reader surmise that this book is about

the physics of life, I attempt an impassioned appeal, in Chapter 2, for

an embrace of modern man's scientific approach to understanding life, and a

rejection of the primitive backwards pull that captures most unwary thinkers.

This appeal provides a foretaste of the spicy sting of chapters found in the

second half of the book.

Since genes are such an essential player in

everything, I found it necessary to include tutorial chapters on genetics. The

first of these genetics tutorials, Chapter 3, presents general

properties of genes, such as how they compete and cooperate with each other,

and have no concern for individual welfare beyond what serves them. The second

genetics tutorial, Chapter 4, explores some subtle properties of genes

that will be needed by later chapters. For example, since in every new

environment some genes will fare better than others, it is useful to think of

genes as being "pre‑adapted" and "pre‑maladapted" to novel

environments. This will be an important concept in considering artisan niches

in the modern world.

Chapters 7 and 8 are devoted to the

brain. The most recent advance in the evolution of the human brain is the refashioning

of the left prefrontal cortex. It is important to view the brain as an organ

designed by the genes to aid in gene survival. Rationality is a new and

potentially dangerous tool created by the genes, and it must be kept under the

control of "mental blinders" to assure that the agendas of other

genes are not thwarted. Competing brain modules, cognitive dissonance, and self‑deception,

are just a few concepts that any sentient must know about when navigating a

path through life's treacherous shoals.

Chapter 11

is a gentle introduction to one of the most misunderstood topics in

sociobiology: "group selection." GS has had a rough time gaining

acceptance partly because it had too great a resemblance to the silly

notion (still embraced by the uneducated) that people do whatever is

good for the species. The mathematics of group selection was started on

a sound footing by Reeve (2000), and finally given a symbolic blessing

by Wilson and Wilson (2007). This last reference joins others in

suggesting that altruism has an unsuspected additional origin rooted in

tribal conflicts, and that it has co-evolved with genes promoting

intolerance for people in out-groups.

In Chapter 12

I combine the new thinking about group selection with something

entirely overlooked by sociobiologists: the role of individuals with

insight to subvert the genetic agenda and in the process influence the

rise and fall of civilizations. I argue that group selection increased

when tribal warfare led to ever‑larger tribes, which required

that its membership be ever‑more subservient to "tribal requirements"

since the entire tribal membership had a shared destiny. But,when group

selective forces were at their maximum during the Holocene,

something new happened that heralded the first‑ever "individual

selection" dynamic. The artisans assumed a leadership role in molding

culture, governance, and opening opportunities for individual

expression of

creative and productive labors that led to a state that we now call

"civilization."

It is inevitable that civilizations arise with

an ambivalent self‑hatred. This is because people whose thinking style is

overly influenced by their "primitive" right brain are naturally

resentful of the world created by those new left‑brain artisans. The new world

order favors the left‑brained artisan (engineer, scientist and other rational

thinkers) and relegates to some vague periphery the contributions that can be

made by the old‑style people. Thus, every civilization should have "two

cultures" that are in conflict, and this is treated in Chapters 13 and 14.

Chapter 19 describes what others now refer to as the Anthropic Principle (I hit upon it in 1990 and

later learned that it had been written about and published obscurely a few years

before). I use this idea to predict an approximate range of dates

for a significant crash in the human population. In the process of calculating this horrific

event, I show that the rate of technological innovations exhibits a trace over

time that foretells population patterns. From this analysis it appears that we

are now in the second major "rise and fall" pattern of innovation rate

and population, the latter pattern being displaced a few centuries after the

first.

In Chapter 21 I begin my "call to

arms" for individuals to emancipate themselves from the genetic grip. All

previous chapters are preamble to this one and those that follow. My appeal

must be qualified by some nitty‑gritty facts of genetics, such as pleiotropy

and polygenes. Nevertheless, I present a litany of "genetic pitfalls"

that any emancipated person should wish to avoid.

Chapter 23 follows naturally from the previous

chapter, since an individual who wishes to pursue an individual‑emancipated

life must do so within the constraints of living in a society where individual

liberation is difficult. When a sufficient number of people awaken to their

enslaved condition, thoughts may turn to a way for them to coalesce in a shared

search for a winning place. I describe utopias and prospects for isolated

enclaves as a path toward a stable community where individual liberation may be

sought. However, I warn that the world is becoming too "small" for

enclaves to remain safe from meddlesome outsiders. Since the door of

feasibility for creating isolated space communities has shut, and since the

earth is already "too small" for self‑sustaining communities to

remain secret, there are no feasible refuges for utopias. I conclude that

today's world will not tolerate the formation of an enlightened society of

liberated individuals, and that those who might wish to live in such a society

must be content with learning how to live a good life as individuals with

secret dreams while being surrounded by an ever‑increasing number of primitive hoi poloi. The "society of the

cognoscenti" will remain dispersed, and may only occasionally recognize

each other during normal encounters.

Chapter 25

is an annotated version of the best essay ever written: Bertrand

Russell's “A Free Man's Worship.” It is an excellent example of how a

liberated person thinks, and I use it to illustrate the point of the

preceding

chapter. Namely, once a person is liberated from genetic enslavement

and free

to choose values to live by that are compatible with the cognoscenti's

insights,

the best that one can hope for is an aesthetic and poetic attitude

toward "existence" that respects the plight of those not fortunate

enough to share these insights. The existentialist need not be a

sourpuss, nor must he become a passive esthete.

The thoughtful existentialist may end up a compassionate humanist with

a lust

for existence!

So now dear reader, if you exist, do take the

following speculations with a light heart; hopefully your thoughts will be led

in directions that are as congenial to your inherited ways of thinking as the

following are to mine.