Bruce L. Gary (GBL) ; Hereford, AZ, USA

Abstract

This web page describes a method for achieving all-sky photometry with an accuracy of ~0.04 magnitude. It employs a procedure that is much simpler to understand and implement than the standard one. Some theoretical background is included so that the reasons for procedures can be understood. For observers content with photometric accuracy no better than ~0.10 magnitude I recommend a different web page (http://brucegary.net/dummies/x.htm) since the all-sky iterative procedure requires a lot of work with manual measurements and spreadseheet analysis. For the observer only interested in "differential photometry" go to http://brucegary.net/DP/

Fundamentals

Observing Strategy Considerations

Iterative All-Sky

Analysis Procedure - Initial System Calibration

Subsequent

All-Sky Photometry

Differential Photometry

(another web page)

INTRODUCTION

If the earth didn't have an atmosphere that absorbs starlight then all-sky

photometry would be trivial. The observer would merely take a CCD image of

a region with well-calibrated stars, then another image of the region of interest

with the same settings. Corrections would still be required for the observing

system's unique spectral response, but these "transformation corrections"

would be straightforward since they wouldn't depend on air mass or weather

conditions.

Some observers frequently encounter the need for an accurate magnitude

scale in a region devoid of well-calibrated stars. For example, asteroids

are constantly moving through parts of the sky that do not have nearby well-calibrated

stars. Anyone wanting to determine the BVRI spectrum of an asteroid is "on

his own" for establishing accurate magnitudes for stars near the asteroid.

Novae and supernovae are the most common examples of stars that appear where

there are no well-ccalibrated stars. When a bright one of them is discovered

the AAVSO does a good job of quickly preparing a chart with a magnitude

"sequence" that is based on observations quickly-arranged for by a professional

astronomer (Arne Henden) who uses "all-sky photometry" to establish the sequence.

Not every nova or supernova can be supported this way.

Because of the growing number of amateurs with CCD skills conducting projects

that involve accurate brightness measurements there is a growing need to explain

how to perform all-sky photometry. I have encountered enough situations where

I needed to create my own "photometric sequence" chart that I have been motivated

to learn all-sky photometry techniques. In the process of this learning I

have developed what I believe is a straight-forward method for all-sky photometry.

Maybe it is the same as used by the professionals, but I'll admit to not

having determined this yet.

When I started writing this web page I thought I would try to discourage

amateurs from trying to do all sky photometry. I had many concerns about the

feasibility of an amateur astronomer taking on a task that required sophisticated

observing strategies and data analysis. (This may sound funny, coming from

an amateur, but I spent decades as a radio astronomer and atmospheric scientist,

where I became familiar with atmosperhic extinction and data analysis methods.)

I was especially concerned about the amateur being blindly misled in his

analysis by spatial inhomogeneities and temporal variations of atmospheric

properties (which I had studied before my retirement). I was prepared to

advise amateurs to restrict themselves to "differential photometry," which

is based on a single image of the region of interest. However, while I was

learning to do all-sky photometry for my own projects I developed a procedure

which I now believe makes it feasible for other amateurs to make their own

chart sequences using a version of "all-sky photometry" that I am calling

"Iterative All Sky Photometry." My purpose for this web page has thus changed

from trying to discourage amateur astronomers from doing all-sky photometry

to trying it using a technique that I think is within the reach of many amateurs.

The observer who is impatient may click the link "Observing Strategy" or

"Analysis Procedure" given above. For those wanting some grounding in fundamentals,

however, I begin with a section that reviews atmosphere absorption, as well

as difficulties related to temporal variations and spatial inhomogenieties

of atmospheric properties.

Finally, if your goal is to achieve photometric accuracies no better than

~0.1 mag, I recommend a web page that I prepared for amateurs whose main interest

is asteroid astrometry but who wish to improve over the 1 or 2 magnitude errors

that are commonly prepared by automatic programs (such as PinPoint) for submission

to the Minor Planet Center. This web page can be found at Photometry for Dummies. This

web page is meant for those wanting to achieve 0.04 magnitude accuracy.

Flux

First, imagine that you're out in space, holding a magic "unit surface area" so that it intercepts photons coming from a star. The surface can be a 1 meter square, for example, and its magic property is that it can count photons coming through it for any specified interval of wavelengths, for any specified time interval. Let's give it one more magical property: it can count only those photons coming from a specific star that you designate. We might imagine that this last is achieved by some kind of screen way out in front, having at least the same 1 meter square aperture and located so that the magic surface sees only things from the direction of the star.

This device measures something commonly thought of as brightness, but which astronomers call "flux." Photons of the same wavelength have the same energy, so merely counting photons is equivalent to measureing the energy passing through the magic unit surface. Energy per unit time is power, as in "watts." This magic device measures watts of energy, per unit area, per nanometer of wavelength interval. This is called flux, or a version of flux referred to as Slambda. Let's just call it "S".

Magnitude

If we point our magic unit surface area so that we measure S from one star, then S from another, we'll get two S values: S1 and S2. We can arbitrarily define something called "magnitude difference" according to the following: M2 - M1 = 2.5 * LOG10 (S1 / S2 ).

Let's now arbitrarily assign one star to have a magnirude value of zero.

Then, all stars brighter will have negative magnitudes, and all stars dimmer

will have positive magnitudes. If the flux from that universal reference star

is S0 , then any other star's magnitude will be given by:

Mi = 2.5 * LOG10 (S0 / Si ) Eqn 1

We've now devised a system for describing how many photons pass through a unit surface area, per unit time, per wavelength interval, at a specified interval of wavelengths. And we've arbitrarily devised a dimensionless parameter, called "magnitude," for the convenient statement of that number. Magnitude defined this way is convenient because we don't have to give a long value, such as 1.37e+16 [photons per second, per square meter, between 400 and 500 nanometers]; rather, we can simply say M = 12.62.

But wait, we're not done. The wavelength interval is a crucial part of the measurement, since the measurement will vary greatly as we change wavelength intervals. Let's just call the meaurement for the 400 to 500 nanometer (nm) wavelength region a "blue" magnitude. And we can define "green" magnitudes, and "red" magnitudes, etc, by specifying the wavelength region to be 500 to 600 nm, 600 to 700 nm, etc.

Atmospheric Transmission

Now let's take our magical instrument from outer space down through the atmosphere to the surface of the earth. When we look up, we will count fewer photons. Some of the photons are being absorbed by molecules in the atmosphere, and others are being scattered. The scattering is from two kinds of things: molecules and particles. The molecules scatter in a Rayleigh manner, affecting blue photons most, whereas the particles (also called aerosols) scatter in a way that depends upon the ratio of the wavelength to the circumference of the particle (Mie scattering when this ratio is small, Rayleigh scattering when the ratio is large). At some wavelengths, especially within the "red" band, water vapor molecules absorb (resonant absorption) at specific wavelengths. Ozone molecules also have a preferred wavelength for absorbing photons. For these bands the loss of photons will depend upon the number of water vapor molecules, or ozone molecules, along the line of sight through the atmosphere.

To first order, the loss of photons making a straight line path to the magic unit surface area, located at the surface of the earth, will depend on the following factors:

Blue Rayleigh

scattering by molecules, non-resonant absorption by molecules, scattering

by aerosols

Green Non-resonant absorption

by molecules, scattering by aerosols

Red

Non-resonant absorption by molecules, scattering by aerosols, water vapor

molecules resonant absorption

Let's talk more about the aerosols. They may consist of dust particles, salt crystals that are swollen by varying amounts of absorbed water (these are important at coastal sites), sulphate particles (SO4 molecules stuck together plus with water), volcanic ash in the stratosphere, urban smog, water droplets within clouds, and ice crystals in cirrus clouds. All of these aerosols are capable of presenting angular structure that can pass through a line of sight quickly, such as between the measurement of one star and the next. Even during clear conditions, when the eye cannot see changes in water vapor, the total number of water vapor molecules along a given line of sight can change by a factor of two in less than an hour (personal observation).

The zenith view will usually have the smallest losses. During a typical observing period the entire sky will undergo a uniform rate of change of all of the above factors contributing to loss of photons. Tracking an object from near zenith to a low elevation will cause photon losses to change due to both the increasing amount of air that the photons have to traverse, and due to the changing conditions of the entire air mass in the observer's vicinity. We'll have to come back to this pesky subject later.

If the atmosphere in the observer's vicinity does not change during an observing sesson, then the photon losses will be proportional to the number of molecules and aerosols along the path traversed by the starlight. The losses are exponential, however. Each layer of the atmosphere absorbs or scatters a certain percent of the photons incident at the top of that layer. For example, if the zenith flux is 90% of what it is above the atmopsphere, the 30 degree elevation angle flux (where twice as many air molecules and aerosols will be encountered) will be 90% of 90%, or 81% of the outer space flux. Simple geometery says that:

S(m) = S(m=0) * EXP{-m * tau) Eqn 2

where S(m) is the flux measured for an air mass value "m", S(m=0) is the flux above the atmosphere, "EXP" means take the exponential of what's in the parentheses, and "tau" is the optical depth for a zenith path. Tau, the zenith extinction, can is sometimes assigned units of "Nepers per air mass." (Apologies to astronomers accustomed to seeing air mass represented by the symbol "x"; I'm going touse "m".)

The following figure shows atmospheric transparency for a clear atmosphere with a moderatley low water vapor burden (2 cm, for example).

Figure 1. Atmospheric transmission versus wavelength for typical conditions (water vapor burden of 2 cm, few aerosols), for three elevation angles (based on measurements with interference filters by the author in 1990, at JPL, Pasadena, CA). Three absorption features are evident: a narrow feature at 763 nm, caused by oxygen molecules, and regions at 930 and 1135 nm caused by water vapor molecules. Four thick black horizontal lines show zenith transparency based on measurements made (by the author) with a CCD/filter wheel/telescope for typical clear sky conditions on another date and at another location (2002.04.29, Santa Barbara,CA, SBIG ST-8E, Schuler filters B, V, R and I).

Since zenith extinction changes with atmospheric conditions differences of several percent can be expected on different days. In Fig. 1 the transparency in the blue filter region (380 to 480 nm) differs by ~10% between the two measurement sets. Changes of this order can occur during the course of a night. This may be an unwelcome thought, but it is a fact that careful photometry must reckon with (discussed below).

At my new observing site in Southern Arizona (4660 feet elevation) I have

measured the following extinction constants (2004.10.15):

B = 0.28 magnitude/air mass, or 77 % zenith

transmission

V = 0.16

" or 86

% "

R = 0.13

"

or 89 % "

I = 0.09

"

or 92 %

C = 0.13

"

or 89 % "

(i.e., unfiltered)

Unsurprisingly, a medium-high altitude site in Southern Arizona has less

extinction thatn a coastal site in Southern California.

Hardware Spectral Response

The concept of "spectral response" is important throughout all that is dealt with here, so let's deal with that now. Consider a single observation (or integration) of a field of interest using a single filter. The term"spectral response" refers to the probability that photons of light having different energies (wavelengths) will successfully pass through the atmosphere (without being scattered or absorbed) and pass through the telescope and filter and then be registered by the CCD at some pixel location. This probability versus wavelength, called spectral response, varies with photon wavelength, ranging from zero at all short wavelengths, to maybe 20% (as described below) near the center of the filter's response function, and back to zero for all longer wavelengths. The spectral response will be a smooth function, having steep slopes on both the short-wavelength cut-on and long wavelength cut-off sides of the response function. The entire journey of a photon through the atmosphere, the telescope, the filter, and it's interaction with the CCD chip, where it hopefully will dislodge an electron that will later be collected by the CCD electronics when the integration has finished, can be summarized by "probability versus wavelength" functions, described next.

Assuming the observer is using a reflector telescope, or a Schmidt-Cassegrain with small losses in the front glass corrector, the photon that makes it to ground level has a lossless path through the telescope to the filter. For observers using a refractor telescope, there may be losses in the objective lens due to reflections and absorptions. For a good objective, though, these losses will be small. The remainder of this section deals with what happens to ground-level photons that reach the filter.

Filter Pass Bands

There are two commonly used UBVRI filter response "standards" in use, going by the names Cousins/Bessell and Johnson. Most amateurs use filters adhering to the Johnson response shape. The two systems are essentially the same for UBV, and differ slightly for the R and I filters. Observations made with one filter type can be converted to the other using the CCD transformation equations, so it would be wrong to say that one is better than the other. The choice of one system over the other is less important than a proper use of either one (as Optec forcefully states on their web page). Even filters from different manufacturers differ slightly from each other. The following figure shows a typical filter response for BVRI filters made by Schuler.

Figure 2. Spectral response of a set of photometric quality

filters.

Considering those 500 nm photons coming in from a 30 degree elevation, for which only 67% make it to ground level, they may have another 70% probability of passing through the V-filter, for example. In other words, only 47% of photons at the top of the atmosphere and coming in at a 30 degree elevation angle make it to the surface of the CCD chip.

CCD Chip Quantum Efficiency

Photons that make it through the atmosphere and filter still must reach the CCD chip if they are to register with the observer's image. There's a matter of cover plates, protecting the chip and preventing water vapor condensation, which is a minor obstacle for a photon's journey. The real challenge for photons is to deposit its energy within a pixel part of the CCD chip and dislodge an electron, setting it free to roam where it can be collected and later produce a voltage associated with the totality of electrons collected at that pixel location. The fraction of photons incident upon the CCD that can produce electrons in a collection "well" is the CCD's quantum efficiency. The quantum efficiency versus wavelength for a commonly used CCD chip is shown in the next figure.

Figure 3. Fraction of photons incident upon chip that free electrons for later collection (KAF 1602E chip, used in the popular SBIG ST-8E CCD imager).

Considering again 500 nm photons, of those that reach a typical CCD chip, such as the one used in SBIG's ST-8E, only 40% dislodge an electron for later collection and measurement. For the V-filter, therefore, only 19% of those photons at the top of the atmosphere, coming in at 30 degrees elevation angle, actually get "counted" during an integration under typical clear weather conditions. This number is the product of three transmission functions given in the above three figures. Each filter has associated with it a total transmission probability, and it depends upon not only the filter characteristics, but also upon the atmosphere and the CCD properties. For the system used in this example, the following figure shows the spectral response for photons arriving at a 30 degree elevation angle, under typical weather conditions, going through Schuler filters and being detected by the KAF 1602E CCD chip.

Spectral Response Due to All Sourcse of Photon Loss

The following figure shows the fraction of photons starting at the top of the atmosphere that can be expected to contribute to a star's image for a typical atmosphere conditions, using typical filters and a commonly used CCD.

Figure 4. Response of entire "atmosphere/filter/CCD system" for typical water vapor burden, few aerosols,30 degree elevation angle, Schuler filters and SBIG ST-8E CCD (KAF 1602E chip).

The reader may now understand how it happens that different observers can have different system spectral responses for their specific systems and atmospheric conditions. Two observers may be making measurements ar the same time from different locations and using different filters and CCD imagers, and unless care is taken to convert their measurements to a "standard system" their reported magnitudes would differ. The magnitude differences will depend upon the "color" of the star under observation, as described in the next section.

Different Observers Have Different Pass Bands

To illustrate the fact that different observers can have different pass bands when they're both making B-filter measurements, let's consider two observers working side-by-side but using different filters and CCD. For example, before I purchased a SBIG ST-8E with Schuler filters, I used a Meade 416XTE CCD with their RGB filter set. The Meade B filter was intended for RGB color image creation, not for photometry. Since the filters weren't designed for photometry (as Meade acknowledges) they will require large corrections during the process of converting observations made with them to a standard system. For the purpose of this discussion, illustrating the concepts of filter differences, the Meade 616 filters provide are suitable example of the need to be careful. The next figure shows the "atmosphere/B-filter/CCD" spectral responses.for the two systems under consideration.

Figure 5. Spectral response of different systems. The solid trace consists of a Schuler Bu filter, intended for photometry, and a SBIG ST-8E CCD, whereas the dotted trace is for a Meade B-filter and 416XTE CCD. The response for both systems corresponds to observing at an elevation angle of 30 degrees in a typical, clean atmosphere (2 cm precipitable water vapor). Both response traces are normalized to one at their peak response wavelength.

The Meade system has a spectral response that is shifted to longer wavelengths compared to the Schuler/SBIG ST-8E system. This shift may not seem like much, but consider how important it can be when observing stars with a spectral output that usually is falling off at shorter wavelengths throughout the wavelength region of these filter pass bands. The next figure shows a typical star's brightness versus wavelength.

Figure 6. Spectrum of a typical star, Deneb, having a surface temperature of 4800 K, in relation to the two system's B-filter spectral responses.

When a typical star (such as Deneb, shown in the figure) is observed by both systems, the Meade system is observing "higher up" on the stellar brightness curve, producing a greater spectrum-integrated convolved response than for the Schuler/8E system. (The "spectrum-integrated convolved response" is the area under the curve of the product of the stellar source function with the filter response function.) For example, the ratio of spectrum-integrated convolved responses in this example is 1.137, corresponding to a magnitude difference of 0.14. In other words, the Meade system will measure a blue magnitude for Deneb that is too bright by 0.14 magnitudes, and whatever correction algorithm is used should end up adding approximately 0.14 magnitudes to the Meade system's B-magnitude. Redder stars will require greater corrections, and bluer stars will require smaller corrections.

Corrections of this amount are important, which illustrates the need for going to the trouble of performing CCD transformation equation corrections. Observers using filters intended for photometry use will presumably require smaller corrections than the 0.14 magnitudes of the example cited here. Since it is reasonable to try to achieve 0.03 magnitude accuracy, corrections for filter and CCD differences are an important part of the calibration process.

To the extent that the atmosphere can change the spectral response of an observer's atmosphere/filter/CCD for any of the BVRI configurations, it may be necessary to somehow incorporate "atmospheric extinction effects" into the data analysis procedure in order to assure that magnitude estimates are high quality. For example, Rayleigh scattering grows as the inverse 4th power of wavelength, so high air mass observations will shift the short wavelength cut-on of the blue filter more than the same filter's long-wavelength cut-off. In effect, high air mass observations are being made with a blue filter that is shifted to the red. The effect of this will be greater for red stars than blue stars. A simple method is described in a later section of this web page for performing a first order correction for atmospheric extinction effects.

Extinction Plot Pitfalls

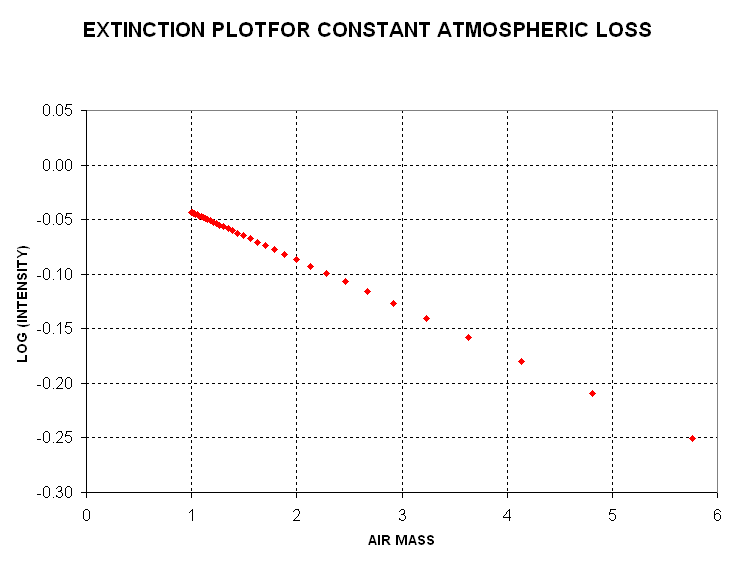

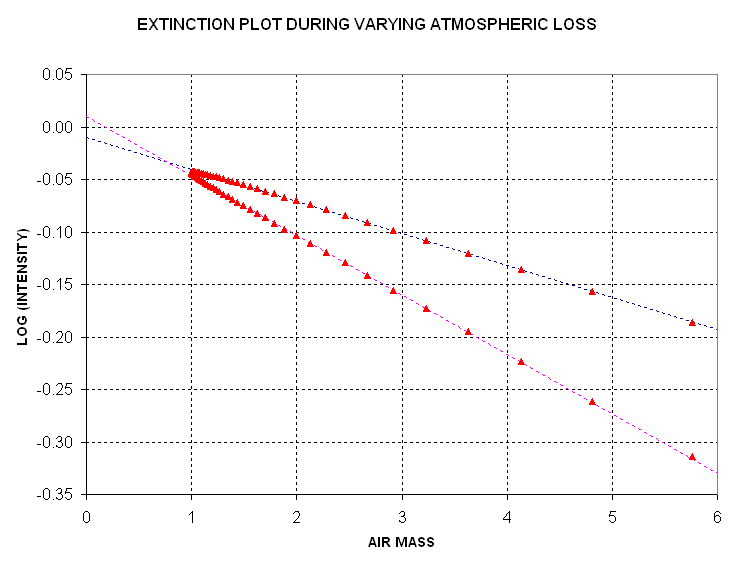

The next pair of figures show what will happen when losses (absorption

plus scattering) vary linearly with time. For simplicity, I have neglected

spatial inhomogenities, which are also going to be present when there are

temporal variations. First, consider a plot of the log of intensity versus

air mass when the atmosphere does not change.

Figure 7. Extinction plot for constant atmospheric losses. It is assumed that Log(I) outside the atmosphere is 0.00 and that each air mass has a loss of 0.1 Nepers (optical depth = 0.1).

An "extinction plot" uses log of measured intensity plotted versus air

mass. If the Y-axis were simply "intensity" then perfect data plots would

be curved; using Log(I) produces straight line plots, which simplifies analysis.

In the above plot the modeled data has a slope, defined as dLog(I)/dm, of

-0.45. The slope is a dimensionless quantity, and it should be the same for

all stars (havng the same spectrum) regardless of their brightness. A slope

of -0.045 corresponds to a transmission of 90% per air mass (i.e.,

10 raised to the power -0.045 = 0.90). Another way of describing this situation

is to state that extinction amounts to 0.11 magnitude per air mass (i.e.,

2.5 * Log (0.90)). Thus, for a view where m=1 the observed star intensity

is 90% of its outside the atmosphere value, at m=1 it is 81% (90% of 90%),

etc. This is a typical extinction value using a V-filter under good sky conditions.

Now consider the same plot but for a linearly temporal change in atmospheric

loss, as might occur when an air mass transition is in progress.

Figure 8. Extinction plot for temporally varying atmospheric

losses. The dashed lines are fitted to rising and setting portions

of the measured intensity.

I've seen this double-branched extinction plot many times during my studies

of atmospheric extinction. One branch corresponds to the rising portion of

data and the other corresponds to the setting portion. If intensity measurements

are made during only one of the branches then a fitted slope would imply an

incorrect extinction per air mass value.

Several properties of the atmosphere can contribute to temporal changes in atmospheric transmission. Sub-visible cirrus (just below the tropopause) that is present in one air mass but not its surroundings is probably the most common source. Volcanic ash can be present above the tropopause (in the lower stratosphere). Volcanoes also eject SO gas, which combines with water vapor to form sulfate aerosols, and these also will be distributed in a non-uniform manner.Water vapor in the lower troposphere is almost always undergoing change at a given site. Vapor burdens (the vertical integral from the surface to the top of the atmospehre) can vary from 1 cm to 6 cm (precipitable water vapor), and I have documented factor of two changes during a half-hour interval at a site in Pasadena, CA. Smog is found near urban sites and the associated aerosols can contribute to large changes in atmospheric transmission. Clearly, some sites will be more prone to these atmospheric transmission changes than other sites. Coastal and urban sites will be worse, generally, but even desert sites will experience some fo the above sources of atmospheric change.

This serves to illustrate that careless observing strategies can produce

extinction plots with misleading slopes, and the slopes are used to derive

atmospheric extinction (Nepers of loss per air mass, or optical depth per

air mass).

I can think of a couopleways to deal with an atmos[phere that is varying

with time. First, restrict all observations to a small air mass range while

alternating between the ROI and standard star fields. Second, alternate

observations of standard star fields that are rising and setting. If this

second approach is used the two stars will exhibit discrepant slopes for the

same air mass region, and this will allow a determination to be made of the

temporal trend as well as an extinction value for the approximate midpoint

of the observations.

I don't want to describe more details of how to process extinction plots

when trends exist, for my purpose here is to simply sensitize the all-sky

photometrist to a problem that is easily overlooked.

This Fundamentals section has described the reasons all-sky photometry

is a challenging task, and I hope it has sensitized the prospective all-sky

observer to the importance of doing it carefully. The next section will give

specific observing strategies that I have found useful in performing all-sky

photometry.

Planning! Before every night's observing session I formulate a plan. This

is especially important for all-sky photometry. Every observer will have their

preferred procedure, but each procedure should address the issues raised in

the previous Fundamentals section. In this section I'll present my preferred

way of all-sky observing.

Assume there's just one "region of interest" (ROI) where a photometric

sequence is to be determined. I use TheSky 6.0 to make a list of the ROI's

elevation versus time. The preferred time to observe is when the ROI is at

the highest elevation, but this is not always possible. For us poor people

who mistakenly bought a German equatorial mount telescope, there's a big penalty

for crossing the meridian. A dozen things have to be changed after a "meridian

flip" and the data on each side of the meridian are not guaranteed to be

compatible. I NEVER do all-sky photometry with my Celestron CGE-1400 using

data from both sides of the meridian. In fact, I always observe on just one

side of the meridian the entire night, photometry or not, and thus avoid

the nuisance of all that "meridian flip" routine. (I'll never buy another

GEM, never! For my diatribe against German equatorial mounts for photometry,

go to http://brucegary.net/CGE/x.htm)

After deciding on the range of time (and elevation) for the ROI observations,

groups of well-calibrated standard stars can be chosen. The guideline for

this is to observe standard stars in such a way that they are observed throughout

the same range of elevations as for the ROI. I try to include at least at

least one group as close to zenith as possible and another as low in elevation

as possible. In addiditon, I try to include groups of standard stars at the

beginning and end of the night's observing session athat are at the same elevation,

preferably near the ROI's low elevation range. This choice will be useful

in assessing the existence of temporal trends.

With TheSky displaying in the "horizon" mode it is easy to see which stars

are at elevations of interest. I often use the Landolt list of well-calibrated

stars for my primary calibration. The Landolt list contains 1259 stars in

groups that are mostly along the celestial equator, as shown in the follwoing

figure.

Figure 9. Locations of Landolt stars. Declination

[degrees] is the Y-axis and RA [hours] is the X-axis. (Note that RA shows

a negative sign, due to a limitation of my spreadsheet program.)

TheSky is able to display this list of stars (with whatever symbols you like) by specifying the Landolt text file's location in the Data/SkyDatabaseManager menu. You can download this Landolt text file from LandoltTextFile.

Since none of the Landolt stars go through my zenith I also depend on

Arne Henden's set of sequences (constructed mostly for the AAVSO, I suspect).

His data can be found at Arne1

and Arne2.

A third source for standard stars is the large database maintained by

the AAVSO. You first have to pick a star that's in the AAVSO chart database

and then download a chart for it. Not all charts are good quality, and only

a few have more than just V-magnitudes, so this data source is inconvenient

Example Observation Session

To illustrate the procedure I use for all-sky photometry I will use an

observing session conducted June 19, 2004 (UT). A Celestron CGE-1400 telescope

was used with a SBIG ST-8XE CCD at prime focus, using a Starizona HyperStar

adapter lens. Custom Scientific B, V and R photometric filters were used.

All images were made with the CCD cooled to -10 C. Focus adjustments were

made several times during the 3-hour observing session. When I'm using a prime

focus configuration the Custom Scientific filters are not parfocal, and this

required that I refocus for each filter change. I used a table of previously-determined

filter focus offsets. Sky conditions were "photometric" and based on atmospheric

seeing of the past few nights and the recent reliability of ClearSkyClock

seeing forecasts for my site, I suspect that the seeing afforded FWHM ~ 2.3

"arc (for a Cassegrain configuration). The prime focus configuration produces

a "plate scale" of 2.8 "arc/pixel, and due to slight distortions caused by

an imperfect prime focus adapter lens I was able to achieve FWHM of no better

than 7.5 "arc. I at least covered a large field of view, 72 x 48 'arc, using

a "fast" system, f/1.86.

The purpose for the June 19, 2004 observing session was to establish a photometric sequence for a cataclysmic variable that had been recently discovered as a suspected nova. The object has a designation of 1835+25 (plus a temporary designation of VAR HER 04). This outbursting binary star is located in the constellation Hercules (about a minute of arc from the border with Lyra), at 18:39:26.2, +26:04:10. The magnitude for the June 19 observations was ~12.7.

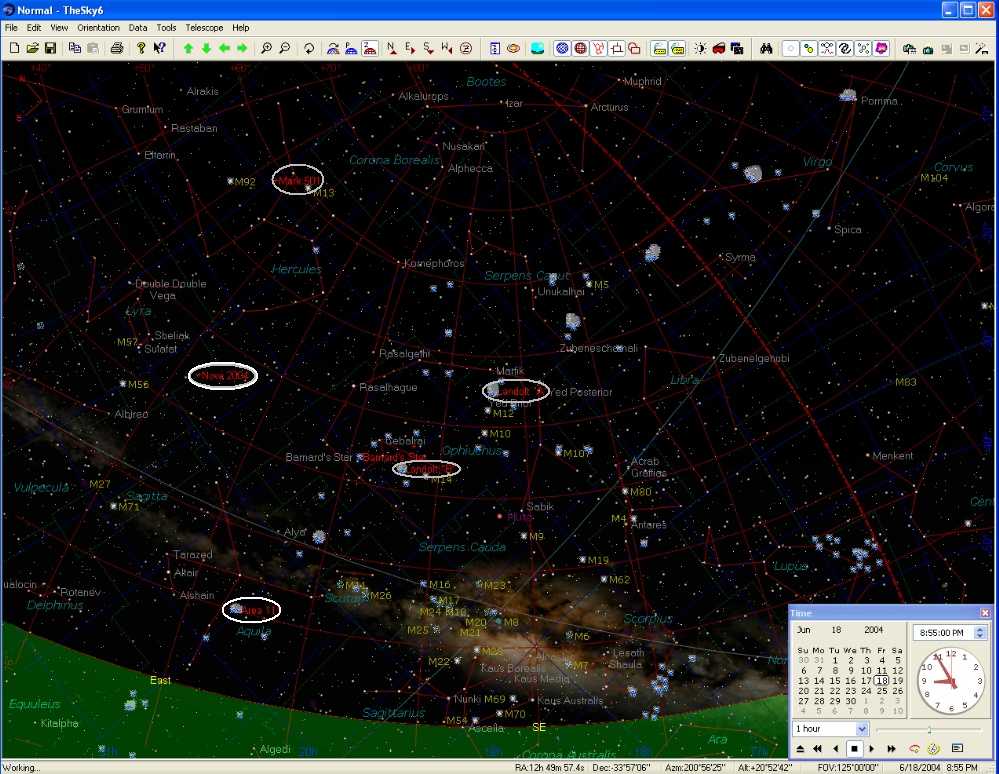

The following figure is a screen shot of TheSky ver. 6.0 showing how two

Landolt star groups and one Arne Hendon sequence (for an AAVSO blazar) were

selected for use to calibrate a star field near the new nova, labeled "Nova

2004".

Figure 10. Resized and compressed screen shot of TheSky

in horizon display mode showing the region of interest ("nova 2004", within

middle-left oval), two Landolt star groups (middle-right ovals), Area 111

(lower-left oval, containing Landolt stars) and an AAVSO chart with Arne Henden

calibrated stars (top-left oval). Other Landolt star groups are shown by

the blue symbols. The meridian is shown by a red dashed trace from the lower-right

horizontothe top-middle border. Elevation isopleths are shown by thin red

traces parallel to the horizon. (The reduced size, compression and conversion

to JPEG greatly degrades readability, made necessary to keep the file size

reasonable.)

Other "planetarium" display programs can probably also be used to select

standard stars (but the TheSky is a great deal and has all the features any

CCD photometrist would want).

After selecting the groups of standard stars to be used as a primary magnitude

standard an observing schedule should be decided upon. Recall the two strategies

described briefly in the previous section for dealing with slowly varying

extinction: 1) restrict all observations to a narrow range of elevations and

alternate observations of standard star regions with the ROI, and 2) alternate

observations of standard star fields that are rising and setting and determine

the trend as well as an average extinction value that can be used with the

ROI observations (made later, earlier or during the standard star observations).

Since my telescope is on a German equatorial mount the second option is

not feasible. Therefore, I always employ the first strategy for dealing with

the possibility of extinction trends during an observing session. For the

observing session being used as my example I decided to start out observing

the "Landolt A" group (right-most oval) and then the ROI (lower-left oval).

This timing places the two targets at about the same elevation, and closely

spaced in time, which means that this pairing will be unaffected by later

assumptions about temporal extinction trends and extinction values. This is

a conservative strategy, and it assures that something useful could be done

with just the first two targets (in case of equipment problems or other show-stoppers

prevented later targets from being observed). It may not have been the best

strategy, but for this observing session I then observed Markarian 501 (upper-left

oval), the ROI, Landolt A, and continued through that cycle until one of

the targets reached the meridian, then an observation of Area 111 at a low

elevation (since it rose late in the night's observing).

Notice that the first Landolt A standard stars and the Area 111 standard

stars are to be made at about the same elevation and are at the beginning

and end of the night's observing session. This makes them an ideal pair for

assessing any trend in extinction value.

My observing plans included a list of things to do before dark. For example,

review the previous observing session log notes to recall if anything anomalous

occurred, review which filters are in the filter wheel (I have a SBIG "pretty

picture" set and a photometric set), review the CCD settings that were last

used (hardware present, flip values, image scale for proper centering), review

the adequacy of the last pointing map, and determine if any telescope reconfiguration

and rebalancing will be needed. For this specific observing session I had

to reconfigure from Cassegrain to prime focus using the Starizona HyperStar

field flattening lens, and this had to be done before dark. This also requried

a rebalance and an approximate refocus using nearby mountains (so that the

flat fields would be at the correct focus setting). I also had to replace

some "pretty picture" filters with photometric filters. My plan had to include

new flat fields shortly after sunset, for each filter, and a completely new

pointing calibration (using MaxPoint). Every reconfiguration and rebalance

requires a new pointing calibration. The plan called for setting the CCD cooler

to a value that could be established quickly (such as +5 degC), prior to

the flat field images of the zenith sky after sunset. The plan also included

a sequence of targets, as well as the brightest star to be included in the

analysis (needed for establishing an exposure time that does not lead to "saturation"

of the brightest star). Users of MaxIm DL 4.0 will recognize some the tasks

listed above. That's the hardware control and image analysis program that

I use.

All pre-target items on the plan were implemented before sunset. After

the flat fields were complete I cooled the CCD as far as possible. I determined

that the night's CCD cooler setting would be -10 degC for the entire night,

since that's as cold as I could get without exceeding a cooler (TEC) duty

cycle of 90%. For all-sky photometry it's absolutely essential to use the

same CCD cooler setting the entire night, and to periodically check that the

cooler duty cycle is not approaching 100% (due perhaps to a warming that could

be caused by sundowner winds for example).

I observed each target field with the B, V and R filters. Each filter had

to be focused differently since my photometric filters are not "parfocal"

when at prime focus (the pretty picture filters are parfocal). An exposure

time had to be determined for use on all targets. This probably isn't necessary,

but that's my current preference. A long exposure would cause saturation for

the brightest stars, rendering them unuseable for photometry. I decided upon

an exposure time of 10 seconds after quickly studying the first V-filter exposure

of a star field with known magnitudes.

While observing I keep an "observing log" with an ball point pen. After

observations have terminated I use only a pencil to add comments based on

recollections. This ink/pencil distinction can help in reconstructing what

really happened months later if a re-analysis or review of the observations

is made. For each exposure sequence I note such things as UT start time, object,

filter, exposure time, guided (by AO-7 image stabilizer) or unguided, focuser

sensor temperature (taped to the telescope tube), outside air tempreature,

wind speed and direction, and sometimes my impressions of data quality as

I calibrate and review images coming in "on the fly." When a focus sequence

is performed I log the focus setting and 6 FWHM readings for a sequence of

focus setting valeus centered on the expected best focus position. As soon

as this set is completed I plot FHWM for the best 3 of each set of

6 FWHM readings, and do a hand fit trace to establish the best focus setting.

I note what the best FWHM value is for the focus sequence, and use that as

a reference to monitor drift away from best focus during later imaging in

order to determine when a new focus sequenmce is needed.

On this occasion, June 19, all standard star fields and the ROI were observed

successfully. Depending upon how tired I am I try to begin data analysis shortly

after observations are completed. Invariably, data analysis is best done

as soon after observations as possible. The memory of odd occurences and

other impressions fade with time, and during analysis all these extra memories

are potentially helpful.

ALL-SKY ITERATIVE PHOTOMETRY

- CONCEPTS AND INITIAL SYSTEM CALIBRATION

I recommend skipping this section and going directly to the next

section: DPIP for Dummies That's where

you can download a spreadsheet has an input section, a simple solve section,

and a target star results section. The rest of this section was written before

I created a simpler algorithm for accomplishing DPIP. I'm leaving the material

in this section in place because eome of it is "instructive" of basic concepts.

Differential photometry with MaxIm DL can be done manually or with a photometry

tool. The photometry tool is preferable because it rejects outliers in the

sky reference annulus. However, for all-sky photometry the needed measurement

is "intensity", and this is not recorded by the photometry tool. (If you're

not using MasxIm DL and your image analysis program doesn't display intensity

as you move the 3-circle pattern over the image, then buy MaxIm DL or a program

that does display intensity.) Therefore, manual readings are required for

each star to be included in the analysis.

It is absolutely necessary to use the same signal aperture size for ALL

manual readings of intensity for an entire all-sky observing session. Small

changes in the sky reference annulus are OK, as are small changes in the gap

annulus - but give careful thought to the signal aperture size before starting

to measure and record intensities.My suggestion is to use the fuzziest image

that you're convinced you need to use and select a signal aperture radius

of ~1.5 times the FWHM of a star that has a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) within

the range 50 to 300. Be certain that the FWHM is for a star that is not saturated

(i.e., that has a maximum counts value less than 40,000).

Raw images should be calibrated using the appropriate dark frames. Flat

frame calibration should also be applied to all images. For each field and

filter and observing sequence, a median combine should be performed...

Star Intensity Readings

When making readings of intensity there is the matter of how to position

the aperture circles. For bright stars (SNR > 50, for example) I use the

position that yields the greatest intensity. For fainter stars I manually

position the aperture circles so that brightest pixels are at the center of

the signal aperture circle. Often a greater intensity reading occurs at one

of more pixels away from this setting, but that is usually due to the sky

reference annulus including a slightly different set of pixels and random

noise can change the sky reference level depending on which pixels are included

in the sky reference annulus. This effect is unimportant for bright stars,

but it can dominate intensity results for faint stars.

Intensity readings are made for all Landolt (and other) standard stars,

as well as a selection of stars in the ROI. These should be noted in a reduction

log (using pencil). Intensity is defined to be the sum of all "extra" counts

within a signal circle, where "extra" means differences with respect to the

average count value within a sky referecne annulus. The sky reference annulus

is separated from the signal circle (aslo called an aperture circle) by an

annulus shaped gap, which allows the signal circle to be kept as small as

possible while preventing the sky reference annulus from "contamination" by

starlight from the star in the signal circle.

Extinction Determination

After all stars have their intensity measured for all images the next step

is to determine an atmospheric extinction for each filter. Considering each

filter in turn, and determine the air mass range for each field. Probably

it is best to choose the field with the greatest air mass range for determining

extinction, for each filter (note: it's OK to use the ROI with unknown star

magnitudes for this purpose). When a star field has been chosen for determining

extinction for a given filter the measured intensities should be entered into

a spreadsheet program (such as Excel).

Figure 11. Extinction plot for one field of stars (the ROI) for

R-filter measurements. Each intensity measurement was converted to "2.5 *

LOG(Ir)" before it was plotted. The slope for each fitted straight line is

-0.19 "2.5 * LOG(Ir)" units per air mass, which was the best fit.

The graph shows that one slope [having units of LOG(I) per air mass],

with offsets for each star, fits all extinction plotted data. A best fit

slope value can be determined by a variety of techniques. I find it useful

to enter trial values for extinction, K [mag/m] or magnitude change per air

mass, into a cell in the spreadsheet and note the average RMS residual fit

between a least squares fit model and all measurements. Each time an extinction

value is entered the spreadsheet calculates a best fit intercept for each

star (using K*mav and sum of 2.5*LOG(I) /N, where N is the number of air

mass obserations and mav is the average air mass; details left to the student).

This "trial and error" procedure is a manual least squares solution for K,

and it should be performed for each filter. Afterwards, there will be a set

of K values for each filter, such as 0.25, 0.20 and 0.15 [mag/m], corresponding

to the magnitude change per air mass for B, V and R filters.

Extinction Trends Evaluation

So far this procedure has not allowed for a determination of extinction

trend. Since the June 19 observing date was planned to have negligible effect

from extinction trends it is not necessary to evaluate it. However, for the

purposes of this web page let us do this using the first and last standard

star fields that were observed at about the same air mass. Since B-filter

measurements experience the greatest level of extinction the B-filter data

can be expected to show a greater effect than the other filter data. However,

for this particular data set there are no pairs of osbervations separated

by a large time span that are at the same air mass. The V-filter data comes

the closest to having similar air mass measurements with a large time span

separating them, so that's the data I'll analyze for an extinction trend.

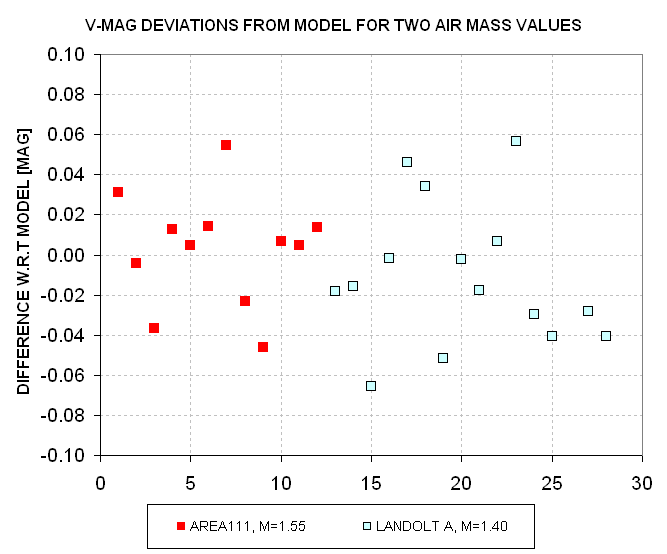

Figure 12. Deviations from extinction model that has no extinction

trend for V-filter observations of Area 111 (m=1.55) and Landolt A (m=1.40)

taken 1.8 hours apart.

The two sets of V-filter measurements appear to fit the same model for

converting intensity, B-V color, extinction and air mass to V-magnitude. The

two data groups deviate from this single extinction model by 0.012 +/- 0.030

magnitude. Taking into consideration their average airmass of 1.47, and the

1.8-hour time span separating them, the two groups of data imply an extinction

trend of 0.004 +/- 0.011 [magnitude per air mass per hour]. This is statistically

insignificant, and the trend, even if it were real, would be 3.0 +/- 7.6

[%/hour] decrease in the average 0.15 [magnitude/air mass] extinction value.

Even if this extinction trend were real it would produce V-magnitude errors

of +0.008 +/- 0.020 at one end of a 3-hour observing interval and -0.008

+/- 0.020 at the other end of the observing interval (for an average air

mass of 1.33). Uncertainties at this level are small compared with the other

uncertainty components, so it is legitimate to assume that extinction was

not changing during this particular observing session.

Converting Intensity to Star Magnitude Using Standard Stars

It is intuitively reasonable to think that a star's measrued "intensity"

(as defined above) contains information about its brightness. Consider the

simplesst possible plot of this, using well-calibrated standard stars, in

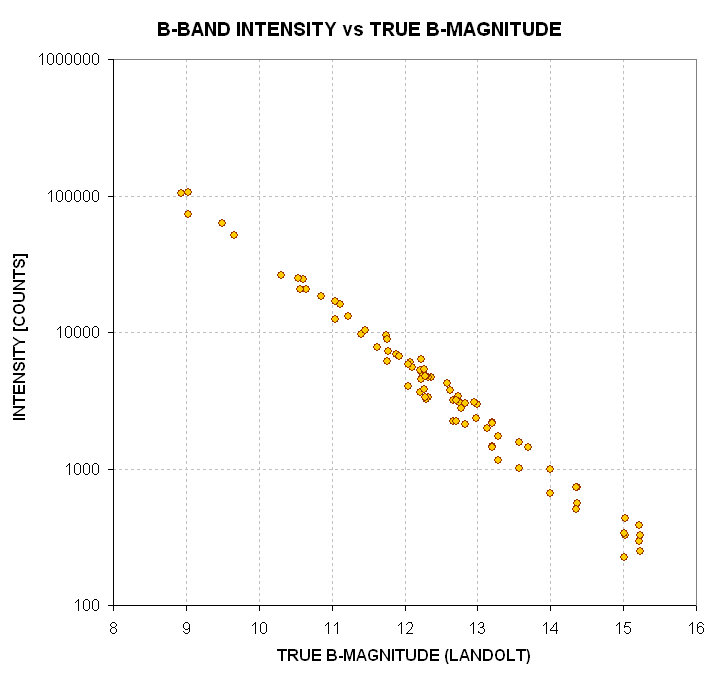

which Intensity is plotted versus true magnitude. The following data is from

an observing session on October 15, 2004, and includes 3 Landolt areas with

a total of calibrated 80 stars.

Figure 13. Measured intensity of standard stars in B-filter images

for 80 Landolt stars (2004.10.15).

Indeed, the intuitive idea that measured intensity is related to true V-magnitude

is borne out by this graph. The graph suggests that we should plot the LOG

(to base 10) of measured intensity versus true B-magnitude. In fact, if we

plot 2.5 times LOG(1/Intensity) we should have a parameter that is closely

related to magnitude, subject to the same offset for all stars.

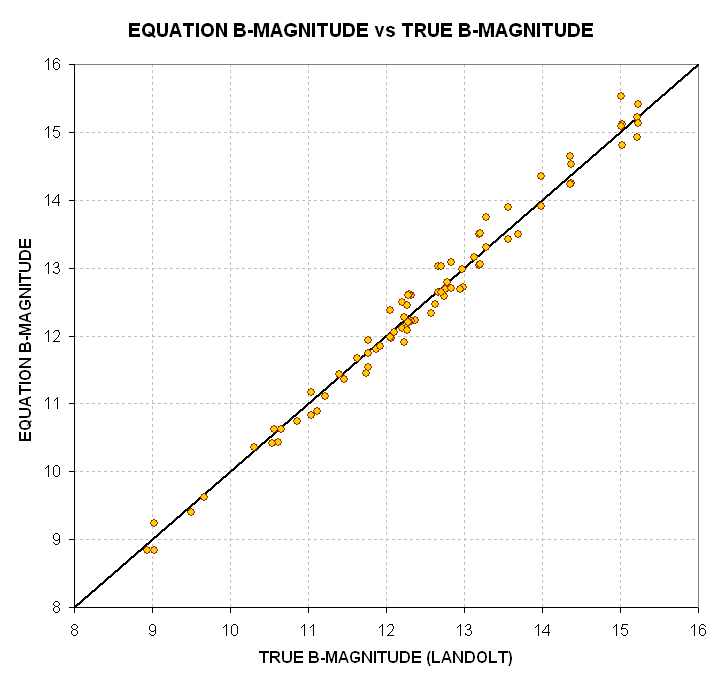

Figure 14. Plot of 2.5 * LOG(Iv) +18.9 (arbitrary offset), labeled

"EQUATION B-MAG" in the graph, using the measured intensities (Ib) of standard

stars in B-filter images.

Sure enough, by playing with arbitrary offsets it was possible to find

an offset value (+19.8) that affords a fairly good correlation of converting

"2.5 * LOG(10/Ib) plus offset" with the true B-magnitudes of the standard

stars. This equation doesn't take into account the different air masses of

the various images from which intensity measurements were made, nor does it

take into account the different colors of the standard stars. The colors should

matter since the observing system has a unique spectral response (caused by

the corrector plate, prime focus adapter lens, filters and CCD response, as

well as the atmosphere). Let's plot the deviations of the above measurements

from the fitted line and see if these differences correlate with air mass

and star color.

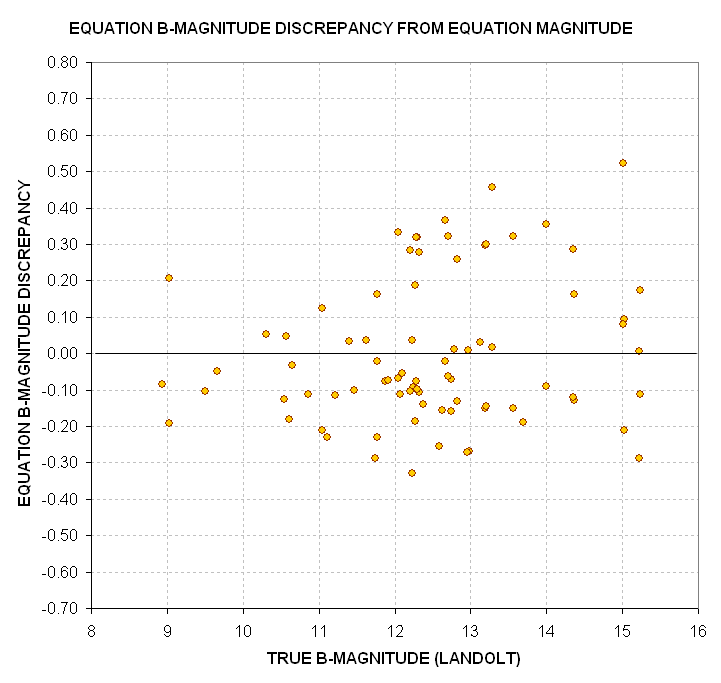

Figure 15. Discrepancies of simple "Equation B-magnitude" versus

True B-magnitude for 80 Landolt standard stars.

The next question we naturally think of asking is "Are these errors correlated

with air mass and star color." We also should ask if there's a statistically

significant correlation with the product "air mass times star color" since

a str's apparent color (entering the telescope aperture is affected by total

extinction). A multiple regression analysis should show whether there is a

signitificant correlation with any of these three independent variables. The

answer is "yes, the errors are correlated with all three independent variables."

The resultant discrepancies are much better "behaved" than those in the previous

figure which ignored these three new independent variables, as the following

graph shows.

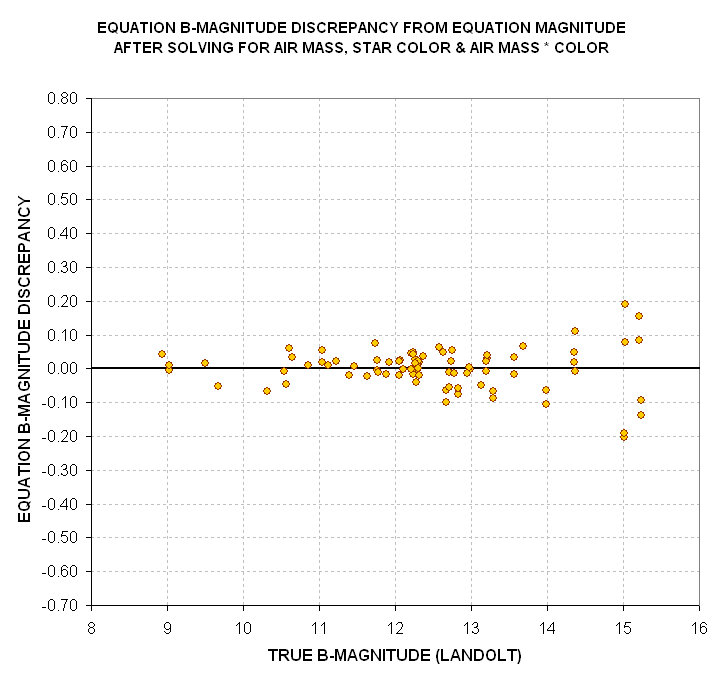

Figure 16. Discrepancies of "Equation B-magnitude" versus true

B-magnitude for 80 Landolt standard stars after solution that uses the three

independent variables: air mass, star color and "air mass times star

color."

The coefficients are +0.229 +/- 0.010 [magnitude per air mass], +0.090

+/- 0.051 [magnitude per B-V mag], and +0.063 +/- 0.027 [magnitude/air mass

times B-V mag]. All three correlation coefficients are statistically significant.

When these correlations are taken into account the simple equation becomes:

Notice that this equation uses 0.64 for a reference B-V star color; this

is the median B-V value for the 1256 Landolt stars in my data base. It will

be convenient to use (B-V)-0.64 as an indepenent variable in order to simplify

analyses for stars with unknown B-V colors (as will be apparent below). Also

notice that the LOG term has "10" in the numerator. This refers to the fact

that the measurements were made with an exposure time of 10 seconds. The reciprocal

of the LOG term is the ratio "Ib/10" and this ratio is merely the rate of

intensity counts per second, which should be the same for all exposure times

(neglecting stochastics).

In this plot the faint stars exhibit a larger scatter than the bright ones,

which is to be expected from SNR (signal-to-noise ratio) considerations.

Using all terms and coefficients derived for this B-band data leads to

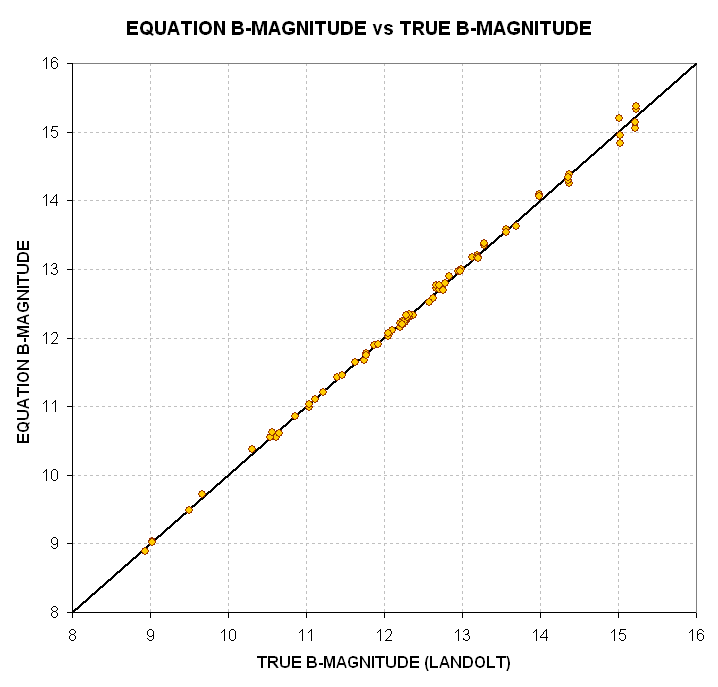

an improved "Equation B-magnitude" as shown in the next figure.

Figure 17. Equation-based B-magnitude (given in text, below)

versus true B-magnitude for 80 Landolt stars. The RMS scatter

for stars brighter than 15th magnitude is 0.043 magnitude.

This figure is to be compared with Fig. 14, which does not contain extinction

or star color terms. Clearly, the extinction and star color are important

independent variables for the task of inferring B-magnitude from measured

intensity. The final equation used for this data set is given below:

Equation B-magnitude = Cb1 + Cb2 * (2.5 * LOG(G/INTb)) + Cb3 * m + Cb4

* ((B-V) - 0.64) + Cb5 * m * ((B-V) - 0.64), where

Eqn 4

Cb1 = 19.31 [mag]

related to telescope aperture, filter width & transmission, dirtiness

of optics (including dew formation), signal aperture size,

Cb2 = 1.00

empirical multiplication factor (related

to non-linearity of CCD A/D converter),

Cb3 = -0.228 [mag/air

mass] extinction for B-filter for the specific atmospheric

conditions of the observing site and date,

Cb4 = +0.097

related to observing system's color

response (i.e., the old CCD transformation equation coefficients),

Cb5 = +0.06

related to product of star color and air mass,

G = exposure time (integration

gate time), seconds

INTb = intensity using

V-filter (integrated excess counts within signal aperture that exceed expected

counts level based on average counts within sky reference annulus), and

m = air mass,

with a residual RMS of 0.043

magnitude (for the 80 standard stars brighter than magnitude 15, air mass

range = 1.19 to 3.04).

Notice that Cb2 isn't necessary because it's 1.00; it is included for the

occassion when stars are included in the analysis that are so bright that

they begin to saturate the A/D converter in the CCD camera causing non-linearities

that affect only the brightest stars.

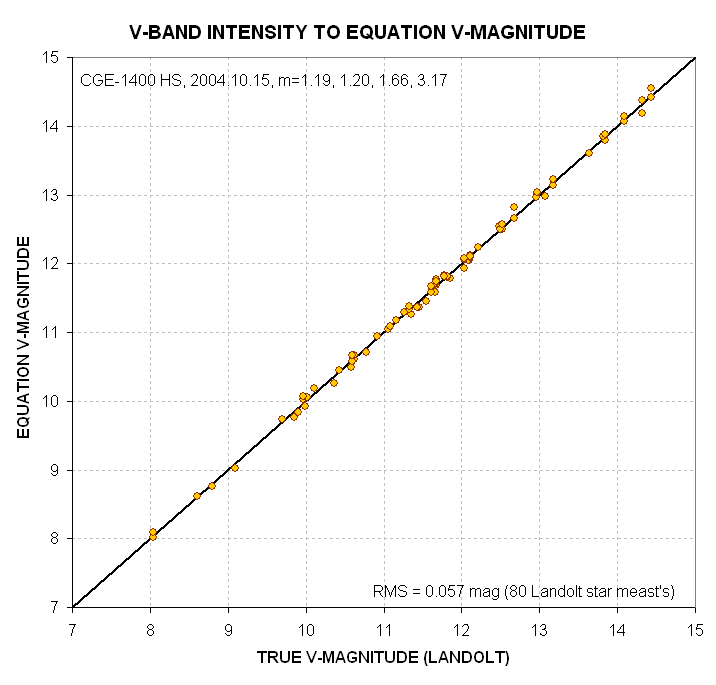

A similar analysis performed for the V-filter data yields the following.

Figure 18. Equation-based V-magnitude versus true V-magnitude

for 80 Landolt stars.

Predicted V-magnitude can be expressed using the following equation:

Equation V-magnitude

= Cv1 + Cv2 * 2.5 * LOG(G/INTv) +Cv3 * m + Cv4 * ((B-V) - 0.64) + Cv5 * m

* ((B-V) - 0.64),

Eqn 5

Cv1 = 19.68 [mag]

related

to telescope aperture, filter width & transmission, dirtiness of optics

(including dew formation), signal aperture size,

Cv2 = 1.00

empirical multiplication factor (related to non-linearity

of CCD A/D converter),

Cv3 = -0.147 [mag/air

mass] extinction for V-filter for the specific atmospheric conditions

of the observing site and date,

Cv4 = -0.145

related to observing system's color response (i.e.,

the old CCD transformation equation coefficients),

Cv5 = +0.06

related to product of star color and air mass,

G = exposure time (integration

gate time), seconds

INTv = intensity

using V-filter (integrated excess counts within signal aperture that exceed

expected counts level based on average counts within sky reference annulus),

with a residual RMS of 0.057

magnitude (for 79 stars and air mass range of 1.19 to 3.17)

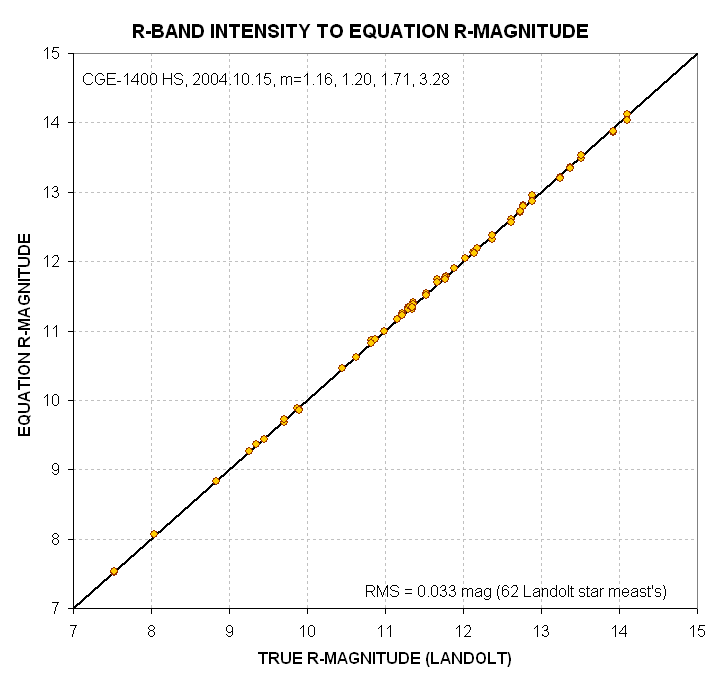

Figure 19. Equation-based R-magnitude versus true R-magnitude

for 62 Landolt stars.

The R-magnitude prediction equation is:

Equation R-magnitude

= Cr1 + Cr2 * 2.5 * LOG(G/INTr) +Cr3 * m + Cr4 * ((B-V) - 0.64) + Cr5 * m

* ((B-V) - 0.64),

Eqn 6

Cr1 = 19.83 [mag]

related

to telescope aperture, filter width & transmission, dirtiness of optics

(including dew formation), signal aperture size,

Cr2 = 1.00

empirical multiplication factor (related to non-linearity

of CCD A/D converter),

Cr3 = -0.100 [mag/air

mass] extinction for R-filter for the specific atmospheric conditions

of the observing site and date,

Cr4 = -0.110

related to observing system's color response (i.e.,

the old CCD transformation equation coefficients),

Cr5 = +0.02

related to product of star color and air mass,

G = exposure time (integration

gate time), seconds

INTr = intensity

using R-filter (integrated excess counts within signal aperture that exceed

expected counts level based on average counts within sky reference annulus),

with a residual RMS of 0.033

magnitude (for 62 stars and air mass range 1.16 to 3.28)

Incidentally, it should be mentioned that unfiltered intensity measurements

can be used to infer V-magnitude. Here's a graph showing how well that can

work.

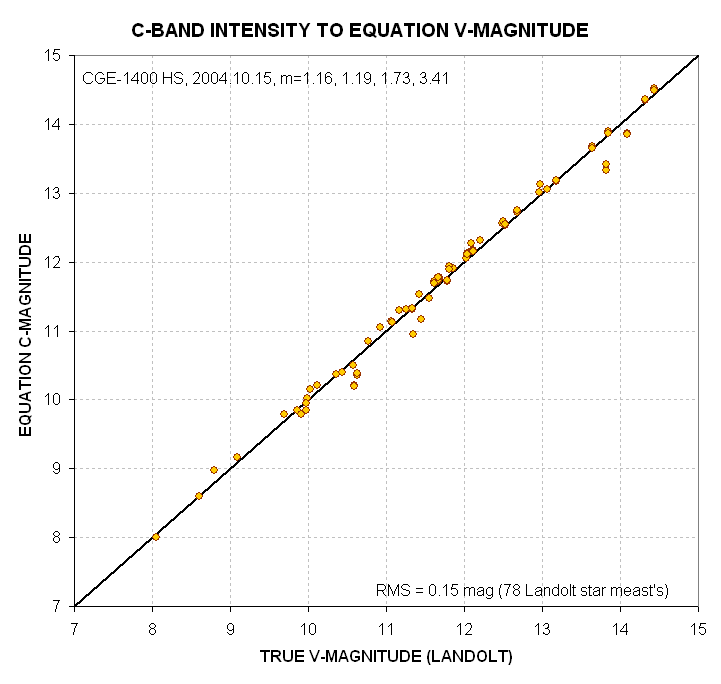

Figure 20. Equation-based V magnitude from unfiltered intensity

measurements, leading to what I'm calling C-magnitude.

The equation for C-magnitude (estimated V-magnitude from unfiltered intensity

measurements) is:

Equation C-magnitude

= Cu1 + Cu2 * 2.5 * LOG(G/INTu) +Cu3 * m ,

Eqn 7

Cu1 = 21.37 [mag]

related

to CCD temperature, exposure time, signal aperture size, telescope aperture,

filter width & transmission,

Cu2 = 1.00

empirical multiplication factor (related to non-linearity

of CCD A/D converter),

Cu3 = -0.100 [mag/air

mass] extinction for clear filter (unfiltered) for the specific

atmospheric conditions of the observing site and date,

G = exposure time (integration

gate time), seconds

INTu = intensity

using no filter (or "clear" filter),

with a residual RMS of 0.15 magnitude

(for 78 stars and air mass range 1.16 to 3.41)

I am surprised that the attempt to infer a V magnitude using unfiltered

intensities, which I'm calling C-magnitude, works as well as this analysis

of 78 Landolt stars implies that it can. Almost all of the 0.15 magnitude

RMS can be attributed to not knowing the B-V star color (if that information

is allowed to be used the RMS becomes 0.054 magnitude). The typical situation

for trying to infer V-magnitude from unfiltered measurements is one in which

no B- or V-filter observations are available, so the 0.15 magnitude RMS performance

is the relevant performance number.

Iterative Procedure for Unknown Region

The previous section shows that if you know a star's magnitude you can

derive it from an image - big deal! This is leading somewhere, though. The

equations, above, state that once you've derived coefficients that work well

for standard stars, it's possible to determine magnitudes for unknown stars

from the following measured properties: intensity, air mass, and star color

(B-V). But for an unknown star even though you can measure its intensity at

a known air mass it doesn't have a known color index, What to do?

Iteration!

Consider the following example (and it's an extreme example since this star is unusually blue).

Star 1835+25 is a cataclysmic variable. During the June 19 observing session

(with exposure times of 10 seconds) it was measured to have the following:

06:33.5 UT m = 1.08 INTb

= 3308 SNR = 141

05:29.6 UT m = 1.23 INTv

= 5830 SNR = 218

Let's convert these measured properties to a V-magnitude (and a B-magnitude).

We'll start by assuming B-V = 0.64, the median value for the Landolt stars . This allows us to calculate approximate B- and V-magnitudes. Using Eqns 4 and 5:

1835+25's B-mag = 19.31 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/3308) -

0.228 * 1.08 +0.097 * (0.64 - 0.64) + 0.06 * 1.08 * (0.64 - 0.64)

1835+25's B-mag = 12.75

1835+25's V-mag = 19.68 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/5830) -

0.147 * 1.23 - 0.145 * (0.64 - 0.64) + 0.05 * 1.23 * (0.64 - 0.64)

1835+25's V-mag = 12.59, so a better estimate for B-V

is +0.16

1835+25's B-mag = 19.31 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/3308) -

0.228 * 1.08 +0.097 * (0.16 - 0.64) + 0.06 * 1.08 * (0.16 - 0.64)

1835+25's B-mag = 12.68

1835+25's V-mag = 19.68 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/5830) -

0.147 * 1.23 - 0.145 * (0.16 - 0.64) + 0.05 * 1.23 * (0.16 - 0.64)

1835+25's V-mag = 12.63, so now B-V = +0.05

The new B-V value departs even more from the standard star typical value,

but at least it changed by only 0.05 magnitude units. Let's adopt this B-V

value for the next iteration.

1835+25's B-mag = 19.31 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/3308) -

0.228 * 1.08 +0.097 * (0.05 - 0.64) + 0.06 * 1.08 * (0.05 - 0.64)

1835+25's B-mag = 12.66

1835+25's V-mag = 19.68 +1.00 * 2.5 * LOG(10/5830) -

0.147 * 1.23 - 0.145 * (0.05 - 0.64) + 0.05 * 1.23 * (0.05 - 0.64)

1835+25's V-mag = 12.64, so now B-V = +0.02

It appears that the changes in V and B-magnitudes are getting smaller

each iteration, and the B-V changes are also getting smaller with each new

iteration. It seems like convergence is occurring. Just one more iteration

is needed (since my spreadsheet shows that no more changes occur after it),

yielding:

1835+25's B-mag = 12.65

1835+25's V-mag = 12.64, and B-V = +0.01

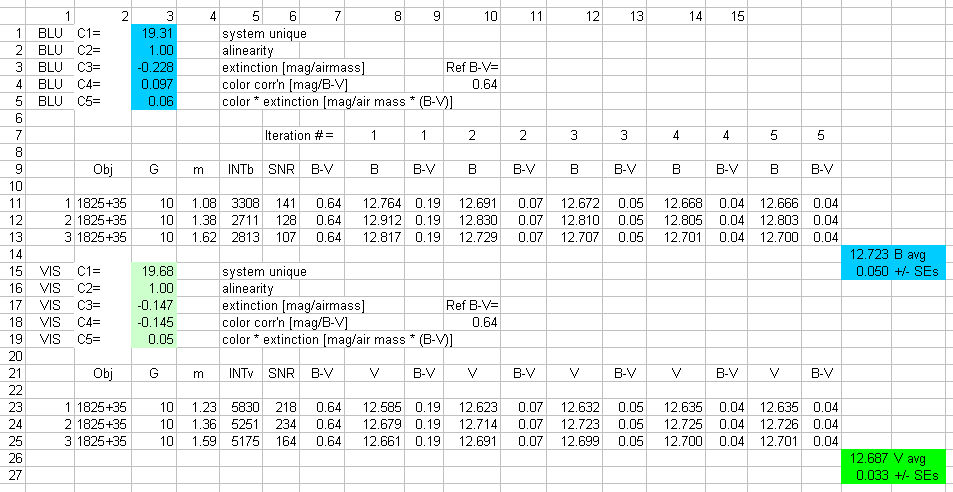

The following figure is a screen capture of an Excel spreadsheet showing how an iteration (involving the above data as one of the three BV observations sets) was performed (effortlessly).

Figure 21. Screen shot of an Excel spreadsheet showing how cells

containing Vand B intensity measurements for each of three data pairs were

automatically calculated once values were entered for m and INTb or INTv.

Rows 1 to 5 contain B-filter coefficients for converting measured B-filter

image star intensity, airmass and color to B-magnitude. Rows 11 to 13 contain

measured intensity for 3 B-filter images having different air mass values.

Rows 15 to 25 are V-band counterparts to rows 1 to 13 for three V-filter

images. The sequence of solutions for B and V-magnitudes is shown in columns

8 through 17. Convergence is apparent. SNR can be used to calculate

stochastic uncertainty SEs, but so can the set of 3 measurements of the same

parameter. Column 18 contains average magnitudes using the converged solutions

and shows the stochastic uncertainty of the averaged magnitudes based (in

this case) on the RMS scatter of column 16 values.

It is apparent that convergence is achieved after 4 iterations. Additional

columns can be inserted if convergence requries it. Rows can be inserted when

more than three images are available for analysis.

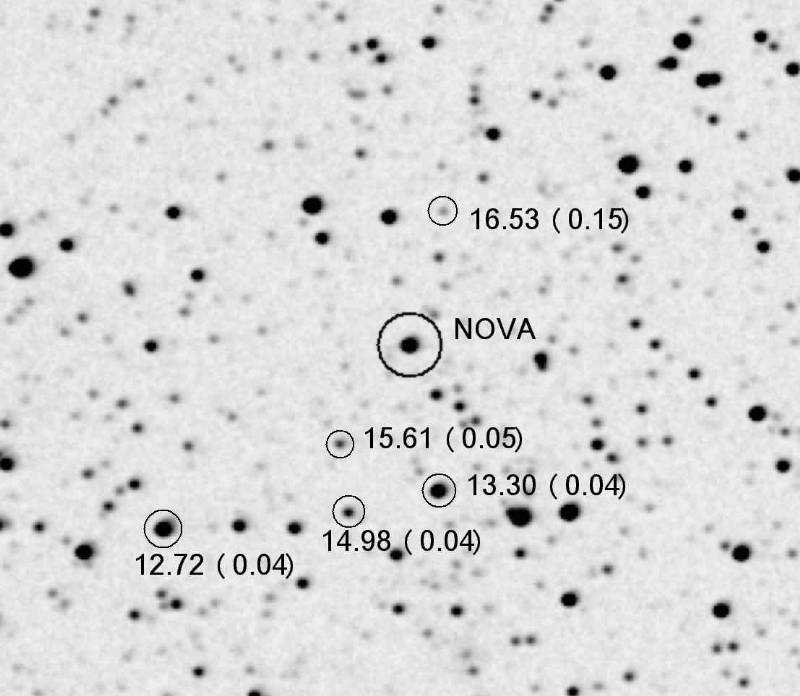

The following image illustrates how the analysis procedure just described

can be used to create a "photometric sequence" for a star field with several

candidate refernce (comparison) stars.

Figure 22. V-magnitudes for the nova's star field. North is up

and east to the left. FOV is 24.8 x 25.1 'arc (EW & NS). FWHM resolution

is ~8.5 "arc. The nova is shown by a rectangle, and at the time of the

images that were used for this average image (June 19.2 UT) the

nova had a V-magnitude of 12.75.

| Object |

V mag |

B mag |

R mag |

B-V |

| 1835+25 |

12.75 +/- 0.04 |

12.65 +/- 0.04 |

12.57 +/- 0.04 |

-0.10 +/- 0.07 |

| Star 1330 |

13.30 +/- 0.04 |

13.89 +/- 0.04 |

12.88 +/- 0.04 |

+0.57 +/- 0.07 |

| Star 1498 |

14.98 +/- 0.05 |

15.78 +/- 0.07 |

14.59 +/- 0.06 |

+0.80 +/- 0.10 |

| Star 1561 |

15.61 +/- 0.05 |

16.19 +/- 0.10 |

14.90 +/- 0.08 |

+0.58 +/- 0.14 |

| Star 1653 |

16.53 +/- 0.15 |

17.20 +/- 0.25 |

15.86 +/- 0.10 |

+0.68 +/- 0.29 |

| Star 1277 |

12.77 +/- 0.04 |

13.17 +/- 0.04 |

12.46 +/- 0.04 |

+0.40 +/- 0.06 |

| Star 1017 |

10.17 +/- 0.04 |

10.70 +/- 0.04 |

9.76 +/- 0.04 |

+0.53 +/- 0.06 |

| Star 0894 |

08.94 +/- 0.04 |

09.46 +/- 0.04 |

8.52 +/- 0.04 |

+0.52 +/- 0.06 |

| Star 1204 |

12.04 +/- 0.04 |

12.42 +/- 0.04 |

11.75 +/- 0.04 |

+0.38 +/- 0.06 |

Figure 23. This is the mysterious

blue star 1835+25 (VAR HER 04). North is up and east is left for both images.

The image is a RVB color image has a FOV = 10.6 x 13.9

'arc, which is a 4% areal crop of a prime focus image taken with

a 14-inch Celestron telescope (prime focus, f/1.86), and the FWHM resolution

is ~8.5 "arc. Notice the very red star north of 1835+25 (having B-V = +1.62,

versus -0.10 for 1835+25).

SUBSEQUENT ALL-SKY OBSERVING

SESSIONS

The previous section describes an initial session for calibrating an observing

system. It produces values for the all-sky coefficients Cb1 to Cb5 (for the

B-filter), Cv1 to Cv5 (for the V-filter), etc. Once this initial calibration

has been performed it is only necessary to re-evaluate one or two coefficients

per filter for subsequent all-sky photometry observations. To understand this,

let's consider the "meaning" for each of the 5 all-sky coefficients, using

Equation V-magnitude as an example.

Equation V-magnitude = Cv1 + Cv2 * 2.5 * LOG(G/INTv)

+Cv3 * m + Cv4 * ((B-V) - 0.64) + Cv5 * m * ((B-V) - 0.64),

Eqn 5

Cv1 = 19.68 [mag]

related

to telescope aperture, filter width & transmission, dirtiness of optics

(including dew formation), signal aperture size,

Cv2 = 1.00

empirical multiplication factor (related to non-linearity

of CCD A/D converter),

Cv3 = -0.147 [mag/air

mass] zenith extinction for V-filter for the specific atmospheric

conditions of the observing site and date,

Cv4 = -0.145

related to observing system's color response (i.e.,

related to the old CCD transformation equation coefficients),

Cv5 = +0.06

related to product of star color and air mass,

G = exposure time (integration

gate time), seconds

INTv = intensity

using V-filter (integrated excess counts within signal aperture that exceed

expected counts level based on average counts within sky reference annulus),

The value for Cv1 will be affected whenever the telesscope configuration

is changed (prime focus to Cassegrain, insertion of a focal reducer, or changing

from a V-filter to a G-filter). As dirt accumulates on the Cassegrain-Schmidt

correction plate, or if the position of cables connected to a prime focus

CCD obstruct different amounts of the aperture, Cv1 will change. When the

seeing changes and a star's FWHM is too large for the user's chosen photometry

signal circle aperture Cv1 may change. For example, if Cv1 was determined

from Landolt star observations in a way that 100% of the point spread function

(PSF) was contained within the photometry signal aperture, and if a new set

of photometry analyses are performed when the seeing was worse (or with a

smaller signal aperture circle), it is possible that not all of the PSF will

be contained within the photometry aperture circle, and this would require

the use of a different Cv1 value. Therefore, every use of Equation V-magnitude

(or Equation B-magnitude, etc) should involve a solution (or quick check)

for Cv1 (Cb1, etc).

Cv2 should be the same for all images since a specific CCD's non-linearity

shouldn't change.

Cv3 is the atmosphere's zenith extinction for the V-band filter, and it

is necessary to re-evaluate this parameter only when the Landolt stars and

the region of interest (ROI) are at different elevations (air masses). The

meaning of "different" in this case depends on desired accuracy. For example,

if zenith extinction can be counted on to vary within the range 0.14 to 0.15

whenever the sky is clear (and clean), then an air mass difference of 0.20

will lead to differences in line-of-sight extinction of 0.030 magnitude. If

this is acceptable, then provided air mass for the Landolt area and region

of interest can be kept the same to within 0.20 then it is not necvessary

to evaluate the night's zenith extinction.

Cv4 is related to the telescope system's unique color response, and provided

the telescope configuration doesn't change (prime focus versus Cassegrain,

for example) it should be safe to adopt the value derived from the all-sky

coefficient evaluation exercise.

Cv5 should undergo a change only when the atmosphere undergoes a large

change in zenith extinction (in which case the sky is not of "photometric

quality"). This term is unrelated to an observer's hardware (to first order),

so unless it shouldn't be adjusted.

Therefore, whenever a Landolt area can be found at approximately the same

elevation angle as the ROI the only coefficient needing re-evaluation is Cv1.When

the Landolt area is more than 0.1 or 0.2 air masses away from the ROI then

two Lanoldt areas at different air masses will have to be observed to allow

evaluation of zenith extinction. If there is reason to believe that zenith

extinction is changing with time then another Landolt area will have to be

observed (separated as much as possible in time) that is at the same approximate

air mass as one of the other Landolt areas.

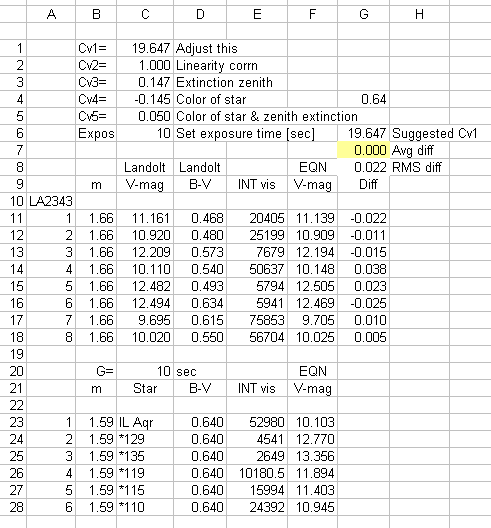

The following figure illustrates how a spreadsheet can be used to easily

convert measured intensity to color-corrected magnitude using a V-filter

image after a one-time observing system initial all-sky calibration.

Figure 23. Example of an Excel spreadsheet section used for

all-sky photometry for converting measured V-band "intensity" to V-magnitude

(once an initial coefficient evaluation has been performed). Coefficients

Cv2 through Cv5 are from the initial all-sky analysis. Cv1 is adjusted by

the user so that Landolt stars (rows 11 to 18) differ from their known V-magnitudes

with an average (cell G7, yellow) that is close to zero. The unknown stars

(rows 23 to 28) are initially assumed to have a B-V color of 0.64, and when

their air mass and measured intensities are entered into the spreadsheet their

equation V-magnitudes are automatically calculated (cells F23 to F28).

This figure depicts an example in which the Landolt star field at RA =

23:43 was observed, and later a region near IL Aqr was observed for the purpose

of establishing a photometric sequence for stars close to the variable IL

Aqr. Only Cv1 was adjusted to achieve agreement (for this observing night)

between the Landolt star Equation V-magnitudes and their known V magnitudes.

In this example the Landolt area and ROI have air mass values that are approximately

the same, and it is not necessary to evaluate zenith extinction.

The same procedure just described for V-filter measurements should be performed

for B-filter measurements inorder to refine the B-V star color assumption.

An iterative process is used to arrive at a stable solution for both V- and

B-magnitudes, similar to that decribed for Fig. 21.

For those occasions that Landolt air mass values differ significantly from the ROI air mass it will be necessary to include observations of an additional Landolt area at a quite different air mass so that the zenith extinction parameter Cv3 can be adjusted. Performing a least squares (LS) solution with a spreadsheet is quite simple when only two independent variables are involved. You simply adjust one parameter to achieve minimum RMS, then change the other independent variable and repeat the RMS minimizing process. Practice helps, as I have determined a global LS solution for as many as 4 independent variables manually with a spreadsheet.

If zenith extinction varies with time, and if the Landolt areas and ROI can't be observed closely in time, then I leave it to the reader to figure out how to deal with this situation.

Return to Bruce's

AstroPhotos

This site opened: June 20, 2004. Last Update: 2012.07.09