GENETIC

ENSLAVEMENT:

A CALL TO ARMS FOR INDIVIDUAL LIBERATION

Third Edition

Bruce L. Gary

Reductionist Publications,

d/b/a

5320 E. Calle Manzana

Hereford, AZ 85615

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Published by Reductionist

Publications, d/b/a

5320 E. Calle Manzana

Hereford, AZ 85615

Copyright 2008 by

Bruce L. Gary

All rights reserved except for brief passages quoted

in a review. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form and by any means:

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without express

prior permission from the publisher. Requests for

usage permission or additional information should be addressed to: BLG Publishing, 5320 E. Calle Manzana; Hereford,

AZ 85615.

Third Edition:

2008 September 12

Printed by Fidlar-Doubleday,

Kalamazoo, MI; USA

ISBN 978-0-9798446-0-7

_________________________________________________________________________________

Books

by Bruce L. Gary

ESSAYS

FROM ANOTHER PARADIGM, 1992, 1993 (Abridged Edition)

GENETIC

ENSLAVEMENT:

A

CALL TO ARMS FOR INDIVIDUAL LIBERATION, 2004, 2006, 2008 (this 3rd edition)

THE

MAKING OF A MISANTHROPE: BOOK 1, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY, 2005

A

MISANTHROPE’S HOLIDAY:

VIGNETTES AND STORIES, 2007

EXOPLANET

OBSERVING FOR AMATEURS, 2007

QUOTES

FOR MISANTHROPES: MOCKING HOMO HYPOCRITUS, 2007

THE

MAKING OF A MISANTHROPE: BOOK 2, MIDNIGHT

THOUGHTS (2008)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

"The topic for today

is: What is reality?"

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Men value

women because they can make babies. Women value men because they can support

and protect a family. The genes value both because their enslavement offers

a prospect for genetic immortality.” Bruce L. Gary

"So free

we seem, so fettered fast we are." Robert Browning,

Andrea del Sarto, 1855

Do you know

what the real question for a thinker is? The real question is: How much

truth can you stand?" Spoken by Nietzsche

character in When Nietzsche

Wept, by Irvin D. Yalom,

1992

"When God

is at last dead for Man, when the last gleam of light is extinguished and

he is surrounded by the impenetrable darkness of an uncaring universe that

exists for no purpose, then at last Man will know that he is alone and must

create his own values to live by." Nietzsche (altered

quotation)

“It’s a privilege to have been born and to live on this planet for a few

decades.” Richard Dawkins, in a debate June 2007

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

C O N T E N T S

Prologue

Introduction

Outlaw Genes in 1962, Uncrossed

Paths in 1963,

Book Overview

1

Reductionism

Universe Rigid, F= ma, No Room for Spirit

Forces,

Dreiser's

"No Why, Only How"

2 Spiritual Heritage

Primitives Need Spirits, We Must Resist

the Backwards Pull

3 Genetics Tutorial ‑ Part I

Review of Earth Life, Competition is Between

Genes, Which

Genes

Compete, Gene Interaction Effects, Trade‑Offs

and

Compromises, Individual Welfare Irrelevant,

Inclusive

Fitness

4 Genetics Tutorial ‑ Part

II

Pre‑adaptation,

Species‑Shaping Forces, How Many Genes

Compete, Pace of

Evolution, Unintended Deleterious

Effects, Dangers

of Fast Evolution, Lag and

Regression, Mutational

Load, Reverse Evolution,

Pleiotropy and Polygenes

5 Genetics Tutorial ‑ Part III

Remote Sensing

Metaphor

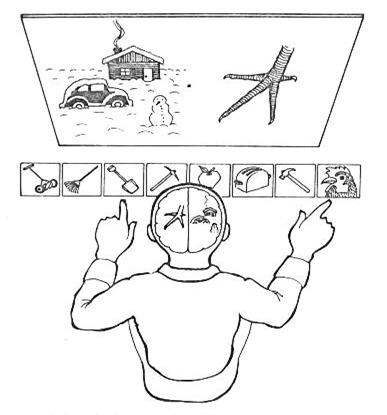

6 Evolution Concepts and Humans

GEP, Men Bear Greater Burden of Selective Forces,

Takeover

Infanticidal Males, Monogamy and Cuckolding,

Men

and Women Shape Each Other, Birth Order,

Duality

of Morality, Emotions Control the Rational,

Consciousness

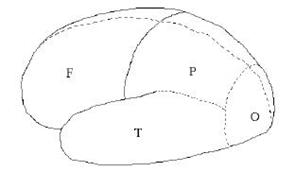

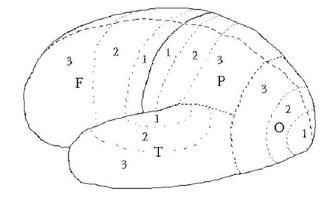

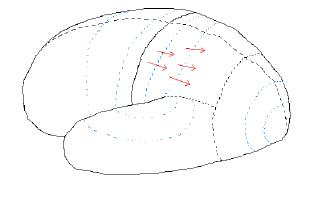

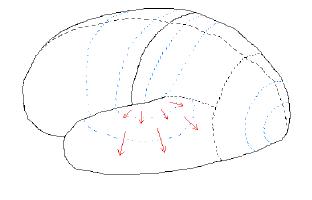

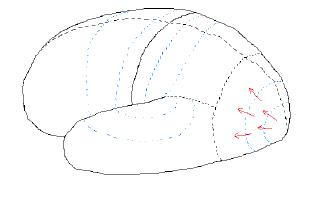

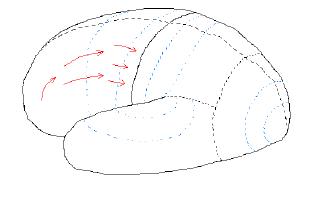

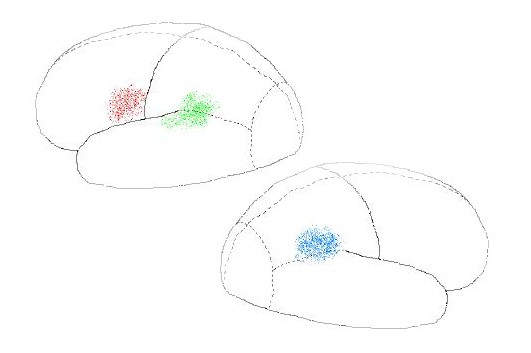

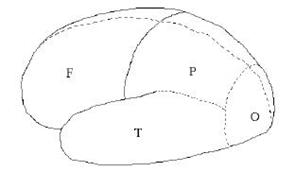

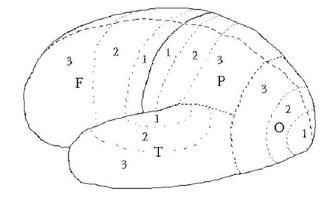

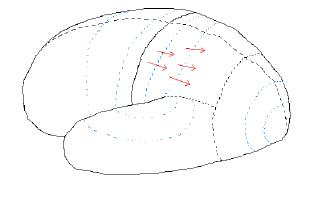

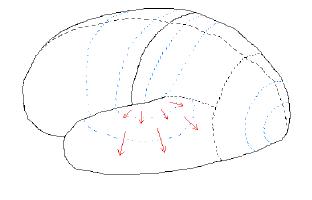

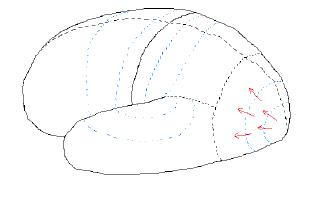

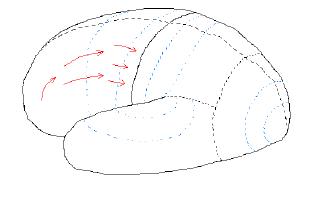

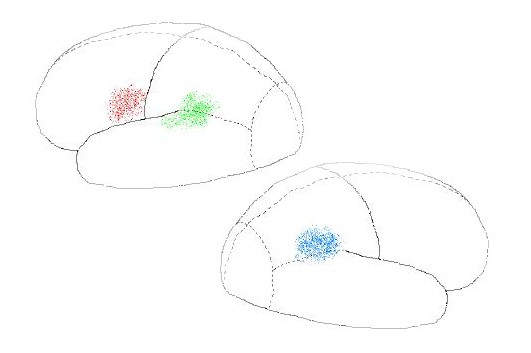

7 Brain Anatomy and Function

Vertical organization, Cerebral Lobes,

Function, Laterality

8 The Brain's Role in Evolution

Prefrontal is Recent, Modules and Genes,

Competing

Modules,

Result‑Driven Thinking, Niches, Individual

Ontogeny

& Species Phylogeny

9 Artisans Set the Stage for Civilizations - Part

I

Tool Making Artisans go Full‑Time, New

Artisan Niches

10 Artisans

Set the Stage for Civilizations - Part

II

Co‑Evolution of Niches and Genes, LB‑Driven

Rise

of Civilizations

11 Lessons from Sailing Ships

Co-evolution of

genes for Altruism/Selfishness and

Intolerance/Tolerance (Group Selection Theory)

12 Levels

of Selection, Rise and Fall of Civilizations

Gene Selection, Group Selection and Individual

Selection,

New Measure for Strength of Selective

Forces,

Rise and Fall of Civilizations, Oscillations

as a Transitional

Mode

13 The

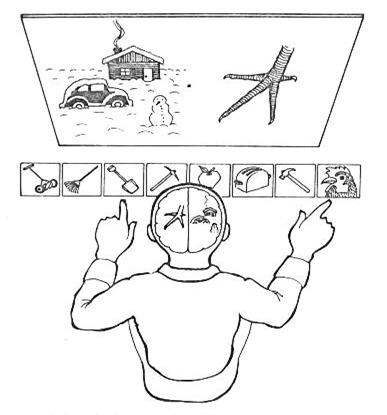

Origins of Two Cultures ‑ Part I

Evolution of a

New Left Brain, "Resentful" Right Brains,

LB/RB conflicts

14 The

Conflicts of Two Cultures ‑ Part II

Example Newspaper Articles,

Example Books, Eastern

Thought,

Fiction and Art, Spiritual Scientists

15 Factors

Influencing Fate of Civilizations – Part I

Natural Catastrophes, Group Selection Theories

16 Factors

Influencing Fate of Civilizations – Part II

Producers/Parasites,

RB/LB Conflicts, Sexual Selection

17 Factors

Influencing Fate of Civilizations – Part III

Troubadours,

Women Speed Civilization’s Fall

18 Factors

Influencing Fate of Civilizations – Part IV

Turning

Inward, Mutation Load (dysgenia)

19 Factors Influencing Fate

of Civilizations – Part V

Fascism Causing Collapse of American Empire

20 Dating the Demise of Humanity

New Time Scale for Humanity, Doomsday Argument

and

Anthropic

Principle, Probabilities of Population Collapse

21 A Global Civilization Crash Scenario

Tribalism's Starring Role; Communism &

Fascism

as

Twin Gene‑Driven Enemies of Artisan‑Created

Civilization,

Genetic Entrenchment and Culturgens,

Conformism,

RB's Revengeful Victory Over LB

22 Living Wisely ‑ Seeking Positives

Mount

Cognoscenti,

Life Dilemmas, Eschewing the

Crowd,

Activity Categories, Emphasize Positives,

Brief

Encounters

23 A Call to Arms ‑ Identifying Outlaw Genes

Prospects

for Replacing Gonad Man After the Crash,

Genetic

Pitfalls

24 Utopias

Isolated Communities, Cognoscenti Societies,

Platonic

Aestheticism

25 Repudiation of the Foregoing

Ultimate Meaninglessness of Everything,

A Hierarchy

for

Dealing With Reality, Existentialism

26 A Free Man's Worship

Annotated

Version of a Bertrand Russell Essay

Your Odyssey

Appendix A: Reductionism

Appendix B: Human

Virus Examples

Appendix C: Remote

Sensing Analogy

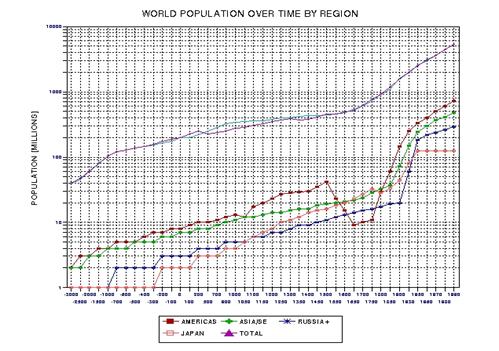

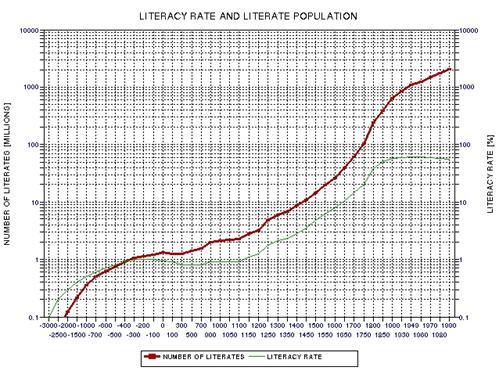

Appendix D: World

Population Equations

Appendix E: More

Repudiation of the Foregoing

References

Index for Authors

Index for Words

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

.

PROLOGUE

"Generally

speaking, it is quite right if great things ‑ things of much sense for men

of rare sense ‑ are expressed but briefly and (hence) darkly, so that barren

minds will declare it to be nonsense, rather than translate it into a nonsense

that they can comprehend. For mean, vulgar minds have an ugly facility for

seeing in the profoundest and most pregnant utterance only their own everyday

opinion." Jean Paul, as quoted

by Friedrich Nietzsche, Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks,

1872.

Dear reader,

you normaloid idiot!

Well, maybe you

deserve an explanation for that greeting.

A perceptive alien

visitor to Earth might report home that humans are the dumbest and most

despicable creatures on the planet!

At least the other

animals don’t claim to know things which, in fact, are absurd nonsense.

Only humans believe in such imaginary things as heaven, hell, guardian angels,

telepathy and all kinds of gods. Only humans maintain that the world was

created by some imagined godly entity just for them and that this God continues

to watch everything and tests humans so that He may reward or punish them

in accordance with how pleased He is by their behavior. Only humans believe

that they are so different from non-living things that their “consciousness”

exempts them from the laws of physics. But the most incriminating human trait

is that homo sapiens is the only species that has itself

for its most dangerous enemy, and a revealing irony is that most killing is

done on behalf of this thing they call “religion.”

Human conceit and

imagination is so poor that people cannot imagine themselves as automatons

that are assembled by genes. Even those few humans who do accept that they

were assembled by genes seem unable to imagine that these genes have achieved

longevity in the species gene pool by assembling automatons that serve

those very genes instead of the individual. This saves them from the indignity

of realizing that they are foolish slaves to tiny lifeless molecules that

use them for aimless ends.

The humans, these

aliens might conclude, are hopeless!

So now, dear reader,

we must have a delicate conversation about you in relation to this book.

If you are like that clueless 99% of humans, those I call “normaloids,” then

let me suggest that you abandon this book and resume your pathetic, unthinking

life! You may do so now! Please do so now!

Are you still reading?

Are you a normaloid pretending to be one of that 1% of thinking humans?

I give you one last chance to feel the guilt of reading something not meant

for you.

Cognoscenti

The following was written for the diminishing numbers

of “the cognoscenti.” And to the cognoscenti who may be holding this book,

I apologize for writing things that are inherently self-evident. You may

have already thought of them yourself, and gone beyond my modest collection

of thoughts. But if, by chance, you have not already discovered the self-evident

ideas in this book then I hope you enjoy the following.

Reductionism

and Hypocrisy

I'm a robot! So

are you! This book views people as robots assembled by genes for the "purpose"

of serving them by behaving in ways that have led to genetic prosperity in

the ancestral environment. Only this “reductionist” viewpoint provides insight

into the many bizarre aspects of human nature.

Every thinking person

should be disappointed in humanity! Indeed, every thinking person should

become a “misanthrope.” In youth it is easy to idealize human nature, to

believe what people say about themselves. Later, perhaps in the teen years,

human hypocrisy is discovered. The so-called “pursuit of Truth” becomes a

hollow promise. Adults who continue to believe in childish notions of human

nature look foolish.

I’m more disappointed

than bitter. I can say that with each year's accumulation of disappointment

in human nature my interest in writing this book wanes. Among the plethora

of book publications there are only a handful for the reader who knows how

to think. Even most of those intended for serious reading are fundamentally

flawed. Why, I keep asking, are so many people incapable

of thinking!

Alas, there is an

explanation; an explanation, indeed, for all the flaws in human nature! We

are the way we are because the genes have constructed us this way because

it serves them!

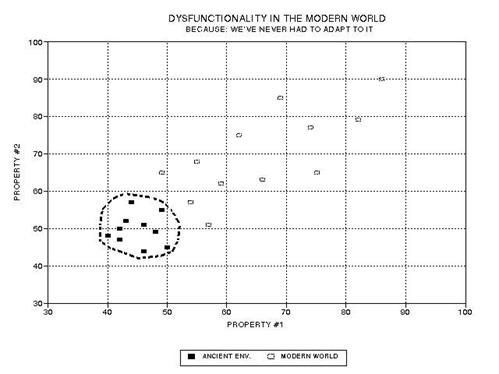

The genes that assemble

us were survivors in the "ancestral environment" (AE). Not only did they

make fools of us in the AE, but in the modern environment our inherited tendencies

make new fools of us in ways that were not even anticipated by the genes.

Anyone who occasionally

glimpses humans this way has the opportunity of choosing a path leading to

a belief that humans are victims of genetic enslavement.

Life takes on new meaning for the person who then wishes for liberation from

that enslavement. This book is dedicated to that rare person already on such

a journey of liberation.

The

mind is a terrible thing to trust

Humans are severely

handicapped at comprehending such things as sub‑atomic strings vibrating

in 11 dimensions, a universe that will expand forever and cause all matter

to "evaporate" in 10100 seconds, or even the everyday experience

of seeing a commercial jet airplane that appears to be 35 degrees ahead of

where the sound is coming from. The list of things we are ill-equipped to

understand is immense!

We cannot readily

understand these things because they never affected the survival of our ancestor’s

genes. How many more aspects of our world are inherently elusive because

they never mattered to genetic survival? Or worse, how many things are hidden

from us because they belong to a category of knowledge that would have adversely

affected the survival of the genes our ancestors carried, even though this

insight might have enlightened the individual?

The layman seems

stubbornly committed to the belief that our minds can be trusted to have

an intuitive understanding of all things. Both the layman and professional

alike will instinctively object to any suggestion that our genes construct

brains that "intentionally" handicap our ability to comprehend the way the

genes have enslaved us. To put it bluntly, I am suggesting that our minds

are designed to steer us away from Truth when alternative false beliefs safeguard

genetic enslavement of the individual, even when this blinded vision diminishes

individual well‑being.

Humanities

versus Physical Sciences

Don't expect humility

from humans. Just as every serious thinker must become exasperated with others,

so should he become exasperated with himself (I use "him" instead of "him/her").

Even within the physical sciences, where I earned a living for 43 years,

it is necessary to consciously maintain vigilance against well‑meaning, intruding

intuitions. Imagine how difficult the task must be within the humanities,

which are blatantly undisciplined compared to the physical sciences. Physical

scientists deal with quantifiable predictions which can be tested by observations.

In the humanities, on the other hand, practitioners seem more concerned

with loyalty to charismatic leaders, and their beliefs, than to the pursuit

of objective truth. Imagine, then, how easily investigations in the humanities

can go astray.

And gone astray

they have! The long endeavor to understand "human nature" has had more false

leads from well‑meaning professionals with social agendas than probably any

other field. For example, some people contend that "human nature" doesn't

exist, believing instead that our minds are "blank slates" at birth, ready

to be written upon for the creation of whatever mental structures conform

to the external world. Others state that “human races” don’t exist, yet insist

on affirmative action preferences for

non-existent minority races. Such beliefs are congenial to

those who secretly wish to fiddle with the social environment for the purpose

of correcting social injustices. Marxist minds are naturally attracted to

the humanities, and have tried for nearly a century to hijack anthropology

and distort it for their purposes.

In spite of the

odds against progress, and in spite of energetic people who seem bent on

leading others astray, there are achievements to be proud of in the study

of human nature. Anthropology and psychology may have a sordid record of undisciplined

meddling by people with political agendas, yet uphill progress in these

fields has surely occurred.

Academic

Quarrels

I recognize that

most readers will object to this misanthropic portrayal of human nature and

my cynical description of "human behavioral scientists." They may be inclined

to agree with some of it, but they will quibble with specifics, or insist

on different ways of approaching the subject. Just as tribes need to fission

when they become too big, major subject areas within academe need to splinter

to form "schools of thought" that go their separate ways by maintaining

petty quarrels. For example, evolutionary psychologists complain about sociobiologists

not having the proper "nuance" concerning adaptation versus optimization,

and they use this minor complaint to build a wall of separation when as

a practical matter the two fields are essentially one.

I am mindful of

the need for petty carping by academics, or the inevitability of it, but

I deplore the loss of vision that it inflicts upon those caught‑up in it.

Sometimes a professional becomes so involved with argument over petty differences,

and concern over whose grant request will be funded, that he forgets to stand

back from day‑to‑day controversies in his field to see it in the larger perspective.

The preoccupation with professional details may render the professional

practitioner blind to bigger visions that can only be seen from a distance.

An outsider, looking in, will occasionally be worth listening to, for he

brings with him that distant "big picture" perspective. I claim to bring

a "big picture" perspective to the subject of sociobiology, and this should

interest the serious lay reader as well as the professional sociobiologist.

This book asks a

lot from the reader without a background in sociobiology, and I realize that

few, if any, will read it through. The professional sociobiologist will readily

understand most of my message, but he will be troubled by the fact that

he does not recall reading other articles by me in sociobiology journals.

The lay reader will not be bothered that my publications are in a totally

unrelated field, but he will find much of the material unfamiliar and will

be repelled by it.

I will not be disappointed

if neither the sociobiologist nor the lay person reads what follows. My life-long

romp in the realm of ideas, and my writing of essays that appear in this

book, has been more fun than what I imagine it would be like to have positive

reader feedback or book sales. Indeed, as of this Second Edition writing

(2006 January) fewer than a dozen of the first edition have been sold.

When

I’m optimistic I recall Henri Beyle (Stendhal), who believed that his writings

would escape notice until a century after his death. His forecast was amazingly

accurate. Such a fate could in theory happen to this little book, but I now

realize that the process of creating it was reward enough. I had more fun

writing it than any reader could possibly experience in its reading. Like

any creation, this book was written for the author.

.

─────────────────────────────────

INTRODUCTION

─────────────────────────────────

BEGINNINGS

OF AN IDEA AND BOOK OVERVIEW

Washington, DC in 1962 was an

exciting place. President Jack Kennedy created a “Camelot” aura that fed

hope for unbounded progress. But the Cuban Missile Crisis brought a sobering

chill to the country, especially to residents of Washington, DC. On my way to work

I'd look north at the Capitol Building and wonder if it

would be blown‑up by a Soviet missile while I was looking at it.

My first job after

college was at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, where I worked as a radio

astronomer specializing in Jupiter's radiation belts. Freed of time‑consuming

college coursework, I was able to broaden my reading. A few years earlier,

the double‑helix structure of DNA had been discovered. Perhaps stimulated

by this, or maybe from the sheer momentum of a childhood fascination with

the way genes influence behavior, I stumbled upon a thought which I now believe

is the second‑most profound one of the 20th Century: “outlaw genes.”

1963 Identification

of Outlaw Genes

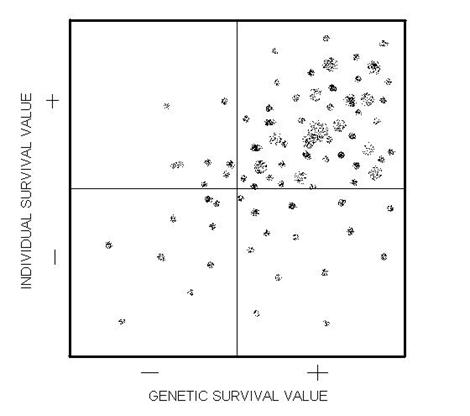

On February 23, 1963 I was imagining

the possibility of categorizing gene mutations as either promoting or subtracting

from their ability to survive into the future and I needed terminology for

this gene attribute. "Gene Survival Value" came to mind. Given a sufficiently

well thought out measurement protocol any gene could theoretically be placed

on a GSV spectrum, with endpoints labeled PGSV and NGSV - standing for "positive

GSV" and "negative GSV." (I recall being dissatisfied with such awkward terms).

At about the same time I was also struggling to devise theoretical concepts

that might guide an individual in choosing a "rewarding life path," as ill‑defined

as such a concept can be in youth. Longevity was one factor, so given the

GSV example I invented ISV, for Individual Survival Value. The ISV extremes,

of course, were PISV and NISV. At this critical juncture, it seemed right

to draw an X‑Y coordinate system, representing GSV and ISV. (In retrospect,

"individual well‑being” would have been a better parameter to adopt than

Individual Survival Value.) The figure on the next page is a rendition of

this scatter diagram.

In theory, any gene

could be "placed" in such a diagram (I hadn't encountered the concept of

polygenes or pleiotropy at that time, to be discussed in a later chapter).

I imagined genes for this and that, and placed them in the diagram. I recall

thinking that there had to be more dots in the upper‑right quadrant, corresponding

to PGSV/PISV.

I realized that

there shouldn't be many dots in the opposite corner since NGSV/NISV mutations

should quickly disappear. Likewise, there shouldn't be many dots in the upper‑left

NGSV/PISV quadrant, though wouldn't it be nice if genes flourished when

they promoted individual happiness regardless of the cost to themselves.

But it was the lower‑right corner that awaited me with a surprise! Gene mutations

of this type would "by definition" flourish while "punishing" the individual

carrying them! And nothing could be done about it, short of replacing the

forces of natural selection with artificially created ones. This gene category

has fascinated me ever since!

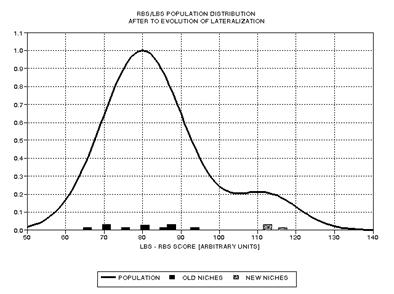

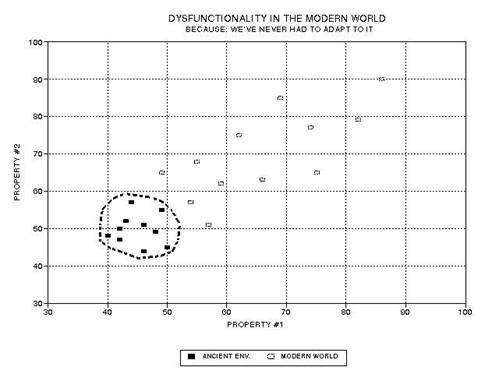

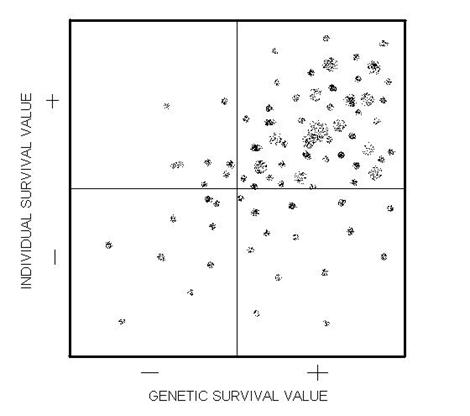

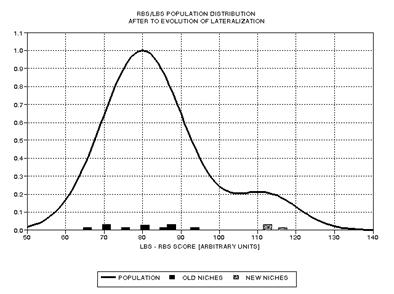

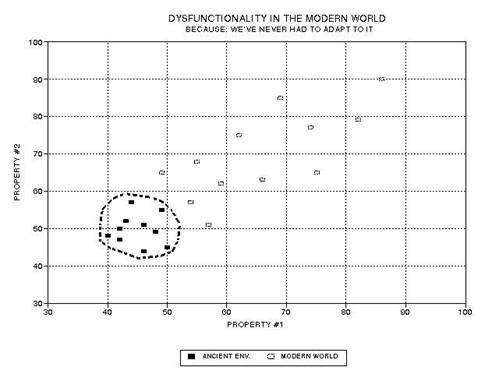

Figure 1.1 An X‑Y matrix

of "genetic survival value" and "individual survival value" with hypothetical

markings of the locus of individual genes (as conceived in 1962).

Why hadn't I read

about such genes? Surely others knew about the inherent conflict between

the individual and some of the genes within! I looked forward to someday reading

about these "outlaw genes," and the philosophical dilemmas they posed. I

stashed these original diagrams and writings on the matter in a file, which

remained closed for decades. Nevertheless, I did not forget about these genes

and during the past four decades I have written about the subject in my

spare time.

Coincidences

In the Fall of 1963 I enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley for graduate studies

in astronomy. As the prospect of taking required courses on such topics as

stellar spectroscopy sunk in, I realized that my career path had taken a

wrong turn, of sorts, since my heart was with the humanities. I managed to

add classes in psychology and anthropology as a consolation for the dry astronomy

stuff. (I quit before semester's end, and have been

gainfully employed in the physical sciences ever since.)

Although coincidences

can shape lives, more often they don't. While I was at Berkeley a little‑known

biologist, George C. Williams, was using the school library to write a

manuscript that would be published in 1966 as Adaptation

and Natural Selection: A Critique of Some Current

Evolutionary Thought. He was making a case for the view that selection

forces work at the level of the genes, not the individual (and definitely

not the species). Although this perspective was inherent in my thinking I

failed at the time to grasp its novelty. I assumed that somewhere in the humanities

was a field in which everyone believed this. Of course I was wrong, for Williams

was engaged in creating such a field.

In this same year,

1963, William D. Hamilton prepared manuscripts describing "inclusive fitness"

(Hamilton, 1964a,b), which is an essential part of understanding how

gene competition drives evolution. The work of both Hamilton and Williams

were essential footings, one decade later, for Edward O. Wilson's milestone

book Sociobiology: The

New Synthesis (Wilson, 1975). In my opinion,

sociobiology is the most important idea of the 20th Century.

I sometimes wonder

how my life's path might have differed if I had met Williams at Berkeley in 1963. A conversation

with him could have clarified for me the emerging nature of the new field,

and the opportunity for a role that I might have played in that emergence.

Although the field was closer to my heart than astronomy, I never ran into

G. C. Williams, and I never realized that he was helping to give birth to

"my" field.

Overlooked Idea

Even now, four decades

later, no one has written clearly about the mischievous genes (to my knowledge).

The Selfish Gene, by Richard Dawkins (1976),

comes close; but it never explicitly states that genes "enslave" the individual

for their selfish advancement while harming the enslaved individual. Mean Genes (Burnham and Phelan, 2000) comes

even closer, but its emphasis is on practical steps for resisting self‑defeating

behaviors rather than the theoretical origins of the genes responsible for

those behavioral predispositions.

Why is there such

a paucity of discussion about the philosophical implications of such a profound

flaw in our origins and present nature? Why have the professional anthropologists,

philosophers and others been so slow to address a subject that captured my

unwavering attention 40 years ago, when I was fresh out of college and struggling

to establish a career in an unrelated field? Sociobiologists have written

about conflicts between competing gene alleles carried by individuals of

various relatedness (Hamilton, 1964a,b), between parents and offspring (Trivers, 1974),

and between siblings (Sulloway, 1996), but not between the individual and

his genes! If any field has a mandate to ask the questions I stumbled upon

in 1962 it is the new field of sociobiology!

If my idea has merit

then sociobiologists have simply overlooked an obvious “next step” in the

unfolding of implications for the basic tenet of the field. The history of

science has many examples of simple yet profound new ideas being overlooked

by the professionals. Every idea has many discoverers, and probably most

of them only half realize the import of their discovery. The oft‑discovered

idea remains out of the public domain until it is grasped by someone having

the energy to push it into the mainstream.

Some of the genes

within us are enemies of the individual, in the same sense that outlaws are

the enemies of a society. This thought should challenge the thinking of

every sentient being. The discipline of philosophy should be resurrected,

and restructured along sociobiological precepts. If this is ever done the

new field would have as its major philosophical dilemma the following question:

"What

should an individual do with the mental pull toward behaviors that are harmful

to individual welfare, yet which are present because they favor the survival

of the genes that create brain circuits predisposing the individual to those

behaviors?"

In other words,

should the individual succumb to instincts unthinkingly, given that the gene‑contrived

emotional payoffs may jeopardize individual safety and well‑being? Or, should the individual be wary of instincts and thoughts

that come easily and forfeit the emotional rewards and ease of living in

order to more surely live another day - to face the same dilemma? Should

some compromise be chosen? How can any thinking person

fail to be moved by these thoughts?

Overview of This

Book

In writing this

book I have wrestled with the desire to proceed directly to the matters of

outlaw genes, and how an individual might deal with them. But every time

I returned to the position that a proper understanding of the individual's

dilemma requires a large amount of groundwork. For example, how can I celebrate

the artisan way of life without first describing why the genes created the

artisan?

In the first edition

of this book I included the many groundwork chapters in their entirety before

the culminating chapters. The first person to read the book (Dr. M. J. Mahoney)

stated that “Once I hit Levels of Selection [Chapter 11] I couldn't

put the book down.” That’s when I realized that I had violated the first

principle of writing, which is to “quickly engage the reader before you lose

them.” In this edition I have shortened the groundwork chapters by moving

most of that material to appendices. The groundwork chapters have become a

primer for the paradigm that leads inevitably to the positions of the main

message of this book.

The remainder of

this introduction is a précis for the book chapters.

There is no guiding

hand in evolution; the natural process of the genes acting on their own behalf

leads to individuals who are mere "agents" for these genes. This is the

perspective of "sociobiology," also called "evolutionary psychology," and

presented most effectively for the general public by Richard Dawkins in

The Selfish Gene (1976). To understand the

"blindness" of evolution one must first understand that the universe is just

a "mechanism," that every phenomenon reduces to the action of blind forces

of physics acting upon dumb particles. This outlook is called "reductionism,"

and is the subject of Chapter 1.

Lest the reader

surmise that this book is about the physics of life, I attempt an impassioned

appeal, in Chapter 2, for an embrace of modern man's scientific approach

to understanding life, and a rejection of the primitive backwards pull that

captures most unwary thinkers. This appeal provides a foretaste of the spicy

sting of chapters found in the second half of the book.

Since genes are

such an essential player in everything, I found it necessary to include tutorial

chapters on genetics. The first of these genetics tutorials, Chapter 3,

presents general properties of genes, such as how they compete and cooperate

with each other, and have no concern for individual welfare beyond what

serves them. The second genetics tutorial, Chapter 4, explores some

subtle properties of genes that will be needed by later chapters. For example,

since in every new environment some genes will fare better than others,

it is useful to think of genes as being "pre‑adapted" and "pre‑maladapted"

to novel environments. This will be an important concept in considering artisan

niches in the modern world.

Chapter 5 is not necessary

for the development of the book’s theme, but for those who understand it

the chapter will provide a deeper insight into the mathematics of pre-adaptation

and pre-maladaptation.

Chapter 6 pulls together

some of the genetics ideas and applies them to human evolution. Certain insights

are needed for a person to intelligently deal with emotions that control

or attempt to discredit intellect. For example, how can a person handle jealousy

without understanding cuckoldry?

Chapters 7 and 8 are devoted to the

brain. The most recent advance in the evolution of the human brain is the

refashioning of the left prefrontal cortex. It is important to view the brain

as an organ designed by the genes to aid in gene survival. Rationality is

a new and potentially dangerous tool created by the genes, and it must be

kept under the control of "mental blinders" to assure that the agendas of

other genes are not thwarted. Competing brain modules, cognitive dissonance,

and self‑deception, are just a few concepts that any sentient must know about

when navigating a path through life's treacherous shoals.

In Chapter 9

I write about the first artisan, whose precarious role as a full‑time tool

and weapon maker may have begun 60,000 years ago. When the climate finally

warmed 11,600 years ago at the start of our present "interglacial," called

the Holocene, the small number of existing artisan roles served as a model

for an explosion of new ones. The new artisans made high‑density populations

possible and eventually led to the creation of civilizations (Chapter 10). Since I will celebrate the artisan way of life

it is necessary to understand how it came into existence and why others in

society are likely to view it warily. I will outline a theory for "anti‑intellectualism"

and suggest that it may play a role in a civilization's decline.

Group selection

still attracts controversy, and I use it argue that tribal warfare led to

ever‑larger tribes, which required that its membership be ever‑more subservient

to "tribal requirements" since the entire tribal membership had a shared

destiny. But, as I argue in Chapter 11, when group selective forces

were at their maximum during the Holocene, something new happened that heralded

the first‑ever "individual selection" dynamic. The artisans assumed a leadership

role in molding culture, governance, and opening opportunities for individual

expression of creative and productive labors that led to a state that we

now call "civilization."

But a civilization

is vulnerable to outside attack by societies that remain uncivilized, that

foster religious fanaticism. These stay‑behind societies harbor resentment

of the material wealth of the civilized society, and instead of achieving

wealth for themselves by surrendering their group‑serving grip on the individual,

they instead mobilize the individual to discredit their rich neighbor and

declare cultural warfare on them. Religious zeal serves these super-tribes

by fostering fanatical, suicidal attacks on those societies that respect

the individual. But since individuals in the civilized society think first

of themselves, the civilization's defense is half‑hearted and ultimately ineffective.

It is inevitable

that civilizations arise with an ambivalent self‑hatred. This is because

people whose thinking style is overly influenced by their "primitive" right

brain are naturally resentful of the world created by those new left‑brain

artisans. The new world order favors the left‑brained artisan (engineer, scientist

and other rational thinkers) and relegates to some vague periphery the contributions

that can be made by the old‑style people. Thus, every civilization should

have "two cultures" that are in conflict, and this is treated in Chapters

12 and 13.

Chapter 14 begins to address

the matter of what factors might contribute to the decline and fall of civilizations.

One theory invokes a back‑and‑forth dominance of artisan "producers" versus

opportunistic "parasites." Another suggests that the two cultures war, or

the “War of the Brain Halves,” is eventually won by those who succumb to

the primitive pull. Gingerly, I also suggest that dysgenia might undermine

our genetic vigor and sap societal energies.

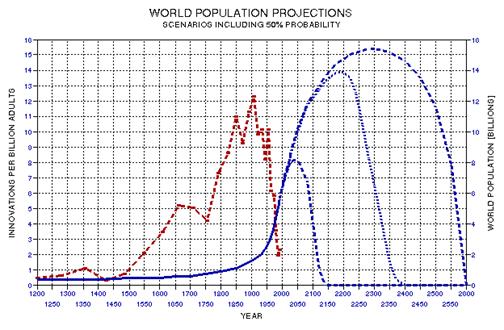

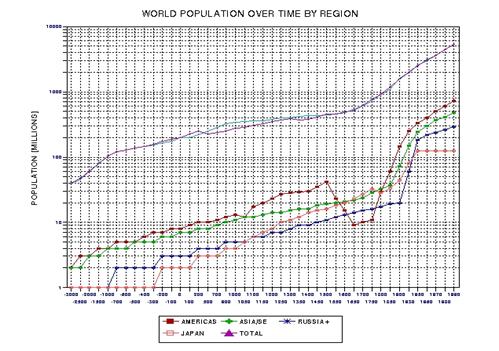

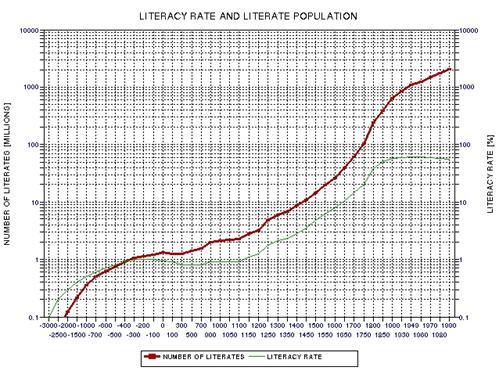

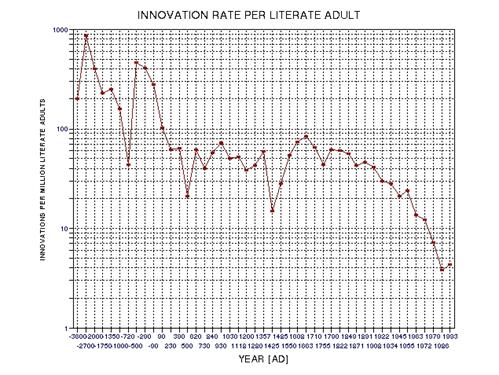

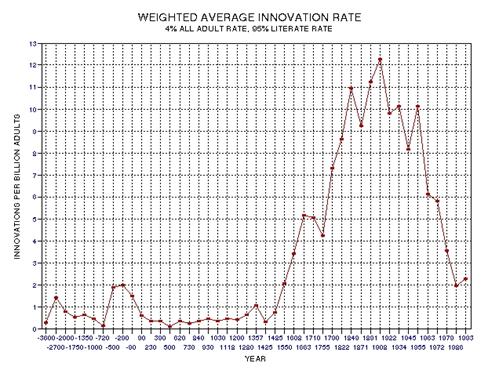

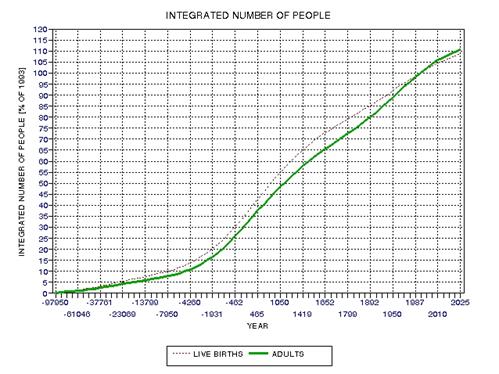

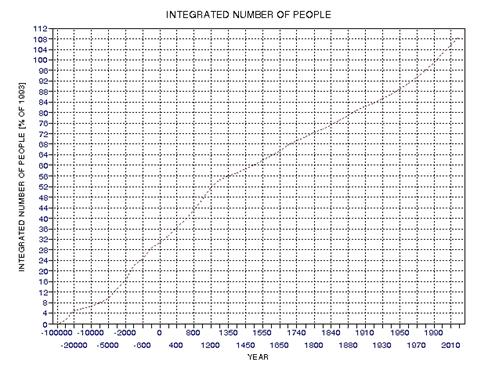

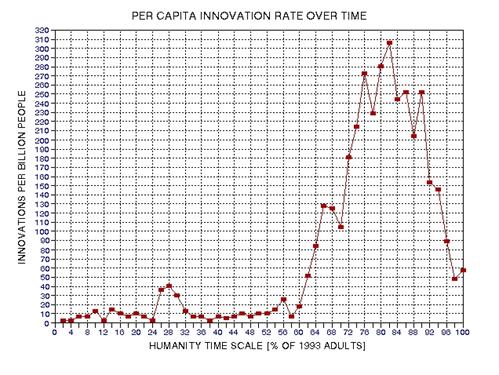

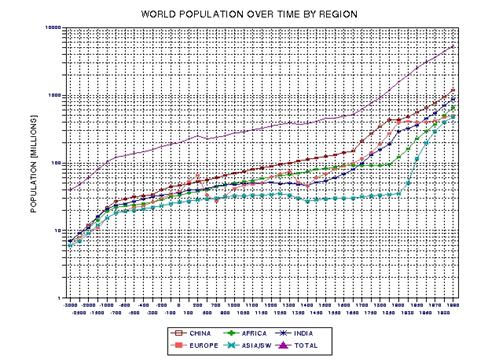

I discovered the

Anthropic Principle (and learned that it had been written about and published

obscurely a few years before my discovery of it). I use this idea to predict

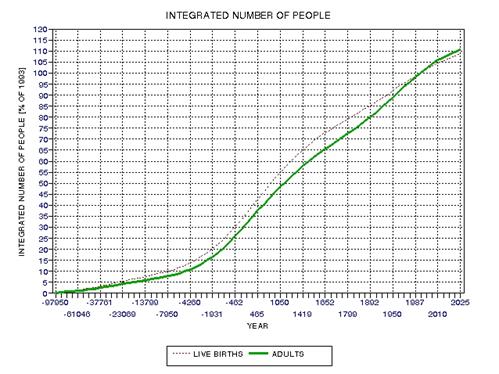

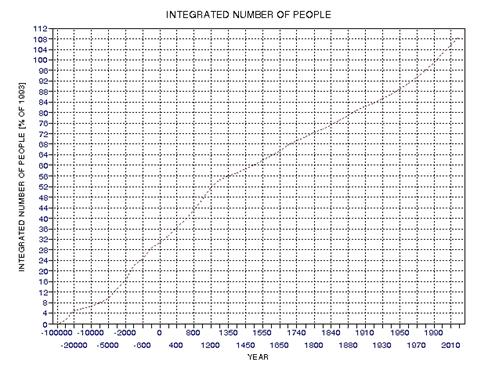

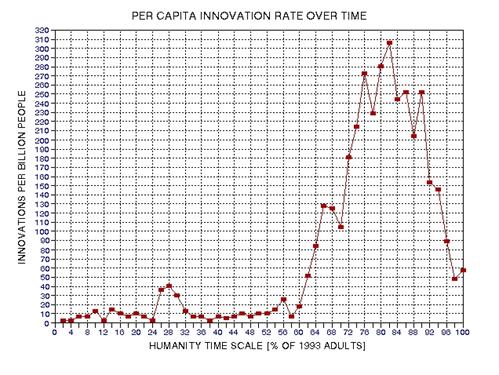

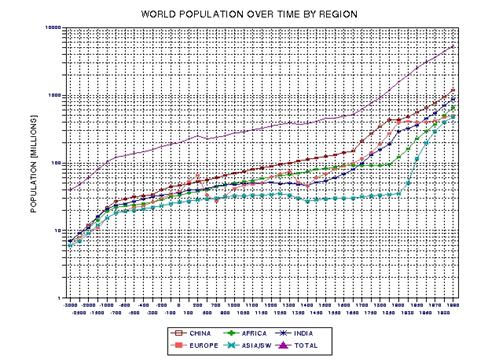

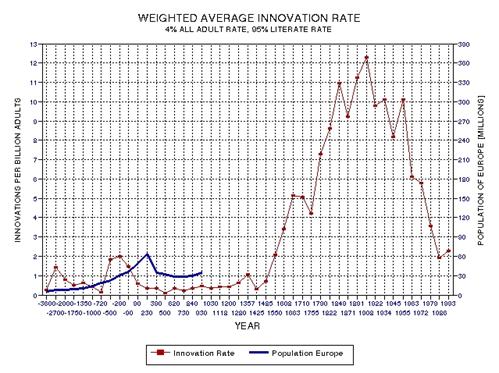

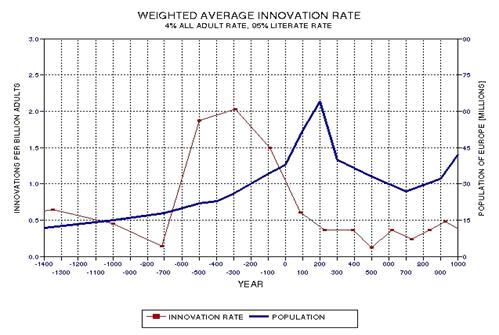

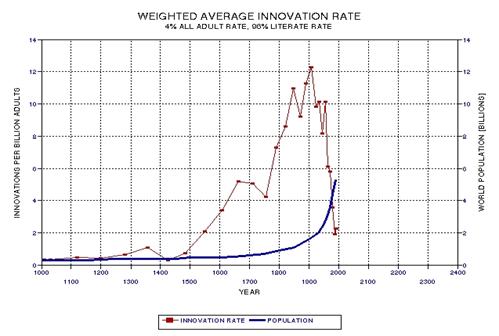

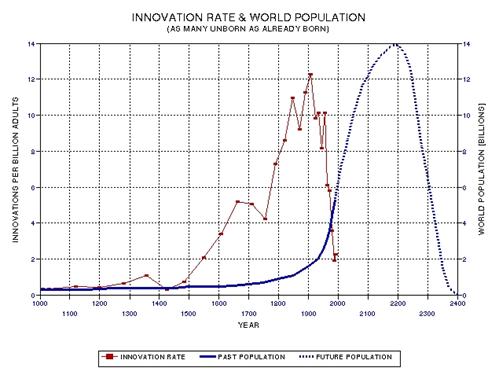

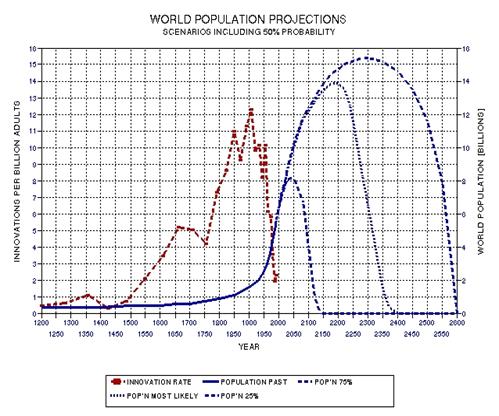

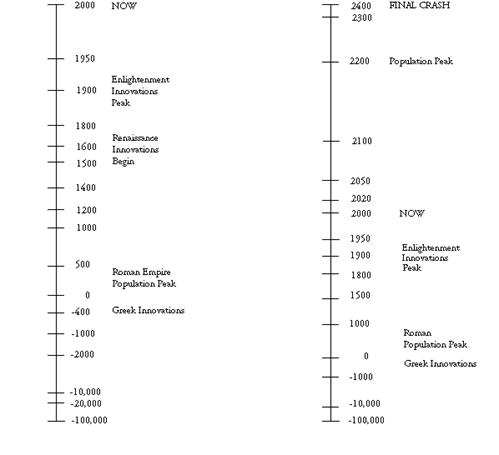

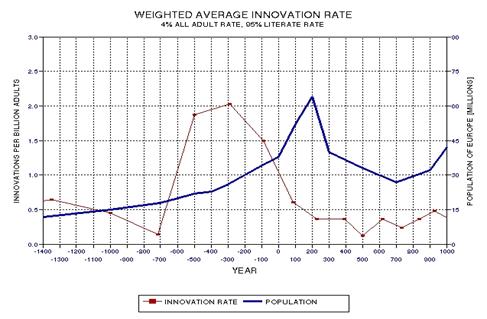

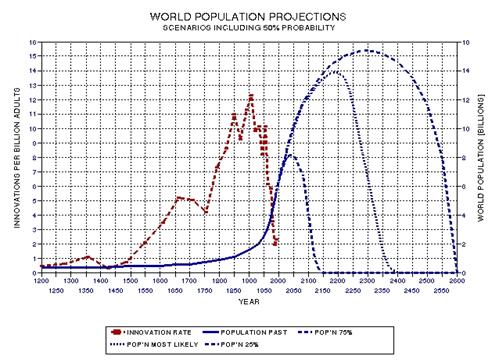

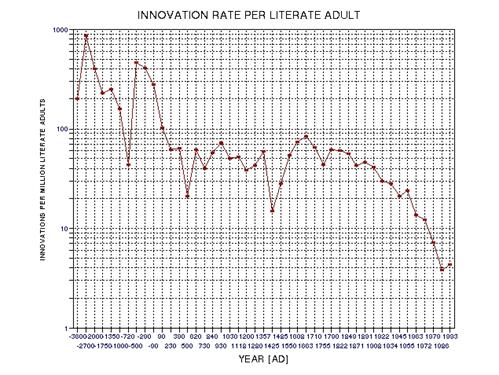

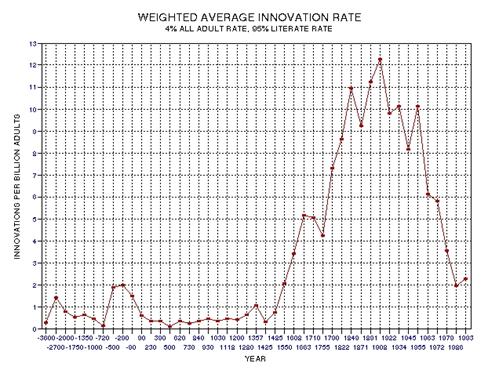

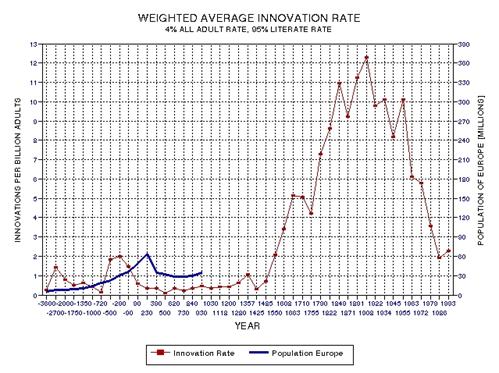

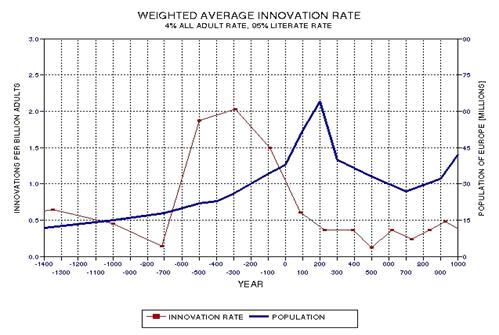

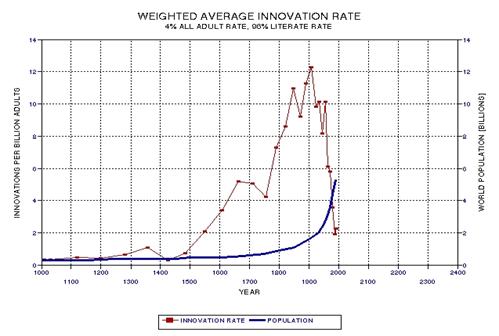

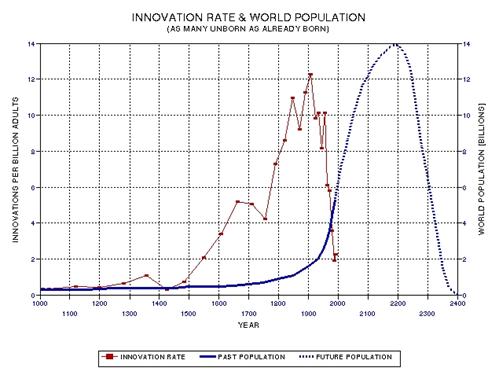

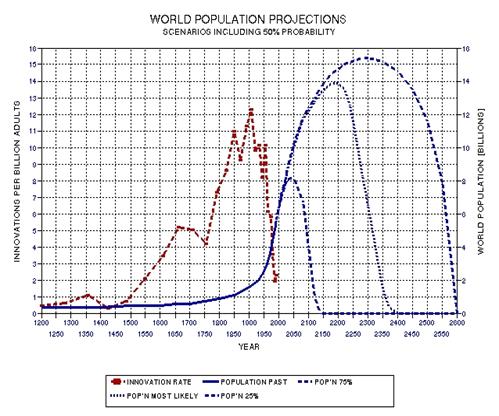

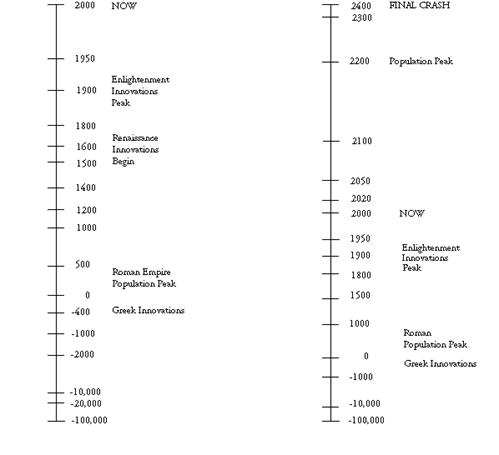

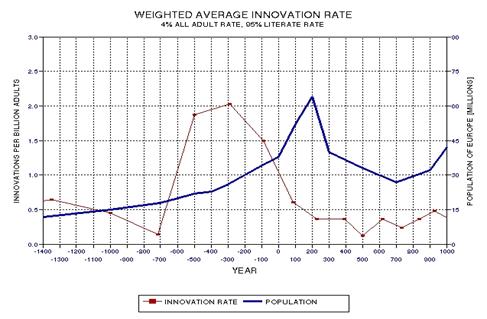

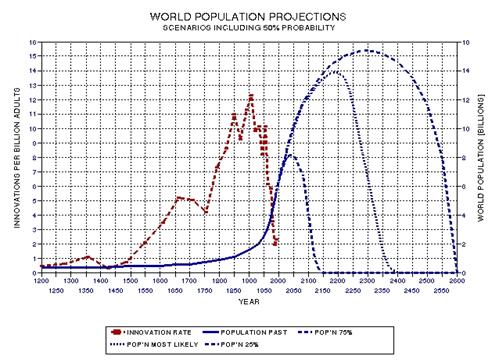

the approximate date range for a significant crash in the human population. In the process of calculating this horrific event, I show

that the rate of technological innovations exhibits a trace over time that

foretells population patterns. From this analysis it appears that we are

now in the second major "rise and fall" pattern of innovation rate and population,

the latter pattern being displaced a few centuries after the first. This

is described in Chapter 15.

I attempt to survey

some possible population crash scenarios in Chapter 16. However, I

conclude that the future is so difficult to predict that it is prudent to

only present possibilities.

In Chapter 17

I begin my "call to arms" for individuals to emancipate themselves from the

genetic grip. All previous chapters are preamble to this one and those that

follow. My appeal must be qualified by some nitty‑gritty facts of genetics,

such as pleiotropy and polygenes. Nevertheless, I present a litany of "genetic

pitfalls" that any emancipated person should wish to avoid.

Because any reader

will expect a book such as this to give specific suggestions for how to use

insight to live wisely, I feel obligated to present in Chapter

18 my feeble attempt to address the subject. It is an attempt to describe

ways that an individual may live wisely in a world wracked with defects caused

by outlaw genes. Some genes are our enemy because they lead to dysfunctional

human societies, while other genes are our enemy because they lead us as

individuals to want the wrong things. The individual's task is to liberate

oneself from the genes, and choose wisely. The IQ form of intelligence allows

insight, and this insight must be placed into the service of an enlightened

"emotional intelligence" to arrive at new personal values to live by. The

questing person will understand the wisdom in the saying, which applies to

the unthinking person: "If you get what you want, you deserve what you get."

However, I readily acknowledge that my attempt to realize this chapter's

goal is feeble, and the reasons for this are developed at the end of the book.

Chapter 19 follows naturally

from the previous chapter, since an individual who wishes to pursue an individual‑emancipated

life must do so within the constraints of living in a society where individual

liberation is difficult. When a sufficient number of people awaken to their

enslaved condition, thoughts may turn to a way for them to coalesce in

a shared search for a winning place. I describe utopias and prospects for

isolated enclaves as a path toward a stable community where individual liberation

may be sought. However, I warn that the world is becoming too "small" for

enclaves to remain safe from meddlesome outsiders. Since the door of feasibility

for creating isolated space communities has shut, and since the earth is

already "too small" for self‑sustaining communities to remain secret, there

are no feasible refuges for utopias. I conclude that today's world will not

tolerate the formation of an enlightened society of liberated individuals,

and that those who might wish to live in such a society must be content with

learning how to live a good life as individuals with secret dreams while being

surrounded by an ever‑increasing number of primitive hoi poloi.

The "society of the cognoscenti" will remain dispersed, and may only occasionally

recognize each other during normal encounters.

Chapter 20 is supposed to

be a surprise, but the subtitle sort of gives it away: Repudiation of the

Foregoing. I will say no more.

Chapter 21 is an annotated

version of Bertrand Russell's essay, “A Free Man's Worship.” It is an excellent

example of how a liberated person thinks, and I use it to illustrate the

point of the preceding chapter. Namely, once a person is liberated from genetic

enslavement and free to choose values to live by that are compatible with

the cognoscenti's insights, an aesthetic and poetic

attitude toward "existence" can be achieved. The existentialist need not

be a sourpuss, nor must he become a passive esthete. The thoughtful existentialist

may end up a compassionate humanist with a lust for existence!

So now dear reader,

if you exist, do take the following speculations with a light heart; hopefully

your thoughts will be led in directions that are as congenial to your inherited

ways of thinking as the following are to mine.

─────────────────────────────────

CHAPTER

1

─────────────────────────────────

REDUCTIONISM

An

intellect which at any given moment knew all the forces that animate Nature

and the mutual positions of the beings that comprise it, if this intellect

were vast enough to submit its data to analysis, could condense into a single

formula the movement of the greatest bodies of the universe and that of

the lightest atom: for such an intellect nothing could be uncertain; and

the future just like the past would be present before its eyes. Pierre Simon Laplace,

Philosophical Essay on Probabilities

(1814).

The

highest object at which the natural sciences are constrained to aim, but

which they will never reach, is the determination of the forces which are

present in nature, and of the state of matter at any given moment ‑ in one

word, the reduction of all the phenomena of nature to mechanics." Gustav Robert

Kirchhoff, 1865.

The idea that all

movement could in theory be reduced to simple laws of nature was first recorded

for posterity by Democritus of Abdera in 4th Century BC Greece. This reductionist

outlook was also expressed by the Roman philosopher Lucretius during the

1st Century BC. After the Dark Ages, when Greek and Roman ideas

lost favor, disillusionment with religion grew among thinkers and they became

curious about the ideas of those ancient challengers of piety and ritual.

Isaac Newton wrote about the forces of nature as a basis for understanding

movement during the 17th Century. The Philosophes

of 18th Century France restored rationalism as the ultimate guide

to Truth. Scientific discoveries continued to provide support to the reductionist

notion, as shown by leading 19th Century scientists such as Laplace

and Kirchhoff.

During the early

20th Century the reductionist paradigm came under challenge by

Quantum Physics. The new physics does not claim to require divine intervention

or primitive spirits, but it does appear to require randomness for events

at physical scales the size of the atom and smaller. The so-called Newtonian

physics is correct as far as it goes, but it cannot explain a category of

physical events associated with the atom and its interaction with light.

At some future time it may be possible to portray quantum physics with the

same deterministic quality as Newtonian physics, but for now it is prudent

to assume that some events are subject to random outcomes. The strict form

of determinism called for by Newtonian physics should be replaced by a probabilistic

form of determinism. However, both forms of determinism are reductionist

since they are based on the notion that the movements of all particles, and

their interaction with light, conform to the laws of physics. This last phrase

is key, “conform to the laws of physics,” and it is dealt with at greater

length in Appendix A.

"Reductionism" either

angers people or delights them. The entire enterprise of science is based

on reductionist tenets. Whereas all scientists practice their profession in

accordance with the reductionist paradigm, there’s a part of the brain that

is so opposed to it that ~40% of scientists claim to not believe in reductionism.

These conflicted scientists are found mostly in the humanities, where muddled

thinking is less of a handicap; within the physical sciences there is almost

universal belief in reductionism (especially among the most esteemed scientists).

The end-point of

reductionist thinking can be most easily described by the following analogy:

the universe is like a giant billiard table, in which all movements are mechanical

‑ having been set in motion by the explosive birth of the universe 13.7

billion years ago! Of course this analogy neglects quantum physics, but

nothing essential to our understanding of the evolution of life, and of

human nature, is lost by this simplification. The march of events, from one

moment to the next, is captured by this simple-minded, deterministic view.

Since this version of reductionism is essential to the rest of this book,

and since it is a fascinating subject in its own right, I devote the rest

of this chapter to a brief description of reductionism and an appendix to

its fuller treatment.

A Rigid Universe

"The Universe Rigid"

was possibly H. G. Well's most important manuscript. It languished with the

publisher, who didn't understand it, and eventually it was lost. Instead

of reconstructing it, Wells turned its central idea into a story, The Time Machine (1895).

Two dozen years

later, Albert Einstein published his Special Theory of Relativity (1920),

which expanded upon the idea, already familiar to physicists of the day,

of time as a fourth dimension. This concept was treated in "The Universe Rigid"

essay with unusual insight, especially for a non-physicist. The following

is a brief summary of it that appeared in The Time

Machine:

"...

Suppose you knew fully the position and the properties of every particle

of matter... in the universe at any particular moment of time:.. Well, that knowledge would involve the knowledge

of the condition of things at the previous moment, and at the moment before

that, and so on. If you knew and perceived the present perfectly, you would

perceive therein the whole of the past. ... Similarly, if you grasped the

whole of the present, ... you would see clearly

all the future. To an omniscient observer ... he would

see, as it were, a Rigid Universe filling space and time ‑ a Universe in

which things were always the same. He would see one sole unchanging series

of cause and effect... If ‘past' meant anything, it would mean looking in

a certain direction; while ‘future' meant looking the opposite way. From the

absolute point of view the universe is a perfectly rigid unalterable apparatus,

entirely predestinate, entirely complete and finished... time is merely a

dimension, quite analogous to the three dimensions of space."

This passage describes

the underlying principle of what is referred to in today's parlance as "reductionism." It leaves no room for spirits, mysticism or gods. Most

intellectuals use the term "reductionist" as a disparaging epithet, but I

believe that reductionism is the crowning achievement

of human thought.

Mechanical Materialism

Reductionism

is the belief that complex phenomena can be "reduced" to simpler physical

processes, which themselves can in theory be reduced to the

simplest level of physical explanation where elementary particles interact

according to the laws of physics. The ancient concept of Mechanical Materialism

captures the essence of reductionism, but relies upon the outdated concept

that at the most basic level the particles are like stones, and interact

by hitting each other like billiard balls.

Nevertheless, reductionism is the fulfillment of what Democritus and Lucretius

dreamed about, a mechanistic world‑view that as a bonus could also deliver

people from the tyranny of religion. Lucretius would agree with the statement:

"There is no need for the aid of the gods, there is not

even room for their interference.... Man's actions are no exception

to the universal law, free‑will is but a delusion." (Bailey,

1926, describing how Lucretius viewed the world).

It will be instructive

to review mechanical materialism before describing the version of reductionism

required by modern physics.

Imagine a game of

billiards photographed from above, and consider frames redisplayed in slow

motion. After the cue sends one ball into motion, the entirety of subsequent

impacts and bounces are determined. If this were not so, if the balls had

a mind of their own, or if some mysterious outside force intervened, then

consistently good players would not exist. Now imagine a very slow replay

of the motions of the billiard balls; millisecond by millisecond the movements

unfold with an undeniable inevitableness. A careful analysis would reveal

that sustained momentum and elastic collisions govern the placement and velocity

of each ball in the next millisecond.

Given two successive

"frames," an observer would know the positions and velocities of every ball,

and he could calculate their placement, velocities and future impacts for

any arbitrarily short instant later. He could thus predict the following

frame, and the process that allowed the prediction of frame 3 from frames

1 and 2 could be repeated for frames 2 and 3 to predict frame 4. And so on,

for all future frames. In this way, the observer could

predict all future movements (don’t worry about the fact that we've ignored

friction).

By a similar process

the observer could infer a previous frame from any two neighboring frames.

Thus, frames 1 and 2 could be used to predict frame 0, etc. Therefore, by

knowing any two frames, all future and past frames could be inferred. This

is the thought H. G. Wells captured with his unpublished Universe

Rigid essay.

Reductionism as

a Basis for Physics

The 19th Century

saw a de‑mystification of various science disciplines. The reshaping was

done by rationalists, building upon the legacy of the 18th Century philosophes. The rationalists firmly placed science on a footing

that has endured throughout the 20th Century. Like the machines of 19th Century

inventors, the paradigm developed by 19th Century scientists was "mechanistic."

Ernst Mach forced

metaphysics out of physics (Holton, 1993, pg. 32). Chemistry was changed

from a floundering quest for transmuting common elements to gold, into a physics‑based

understanding of atoms and molecules. Darwin displaced God from

the creation of life by presenting his theory of evolution, even though this

may have saddened him personally.

By the end of the

19th Century, when Wells began to write, the intellectual atmosphere was

congenial to ideas that reduced mysterious happenings to a juxtaposition of

commonplace physical events. Each event in isolation was conceptually simple.

It is the mere combining of many such events that cause things to appear

incomprehensible.

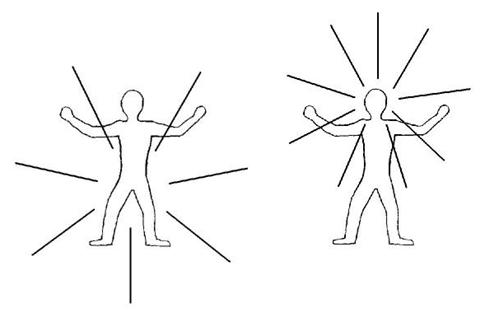

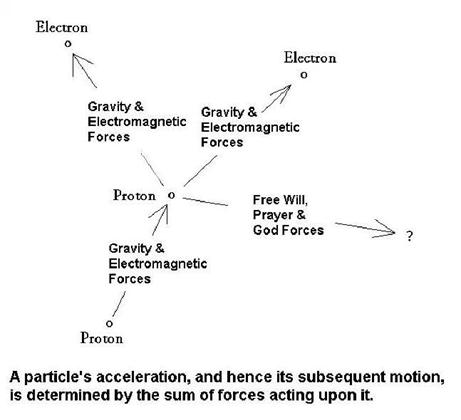

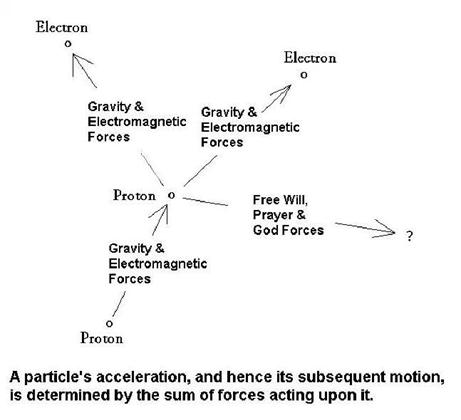

Reductionism is

based on a concept taught in college Physics 101. I remember well that without

fanfare the physics instructor stated that there are only four forces in

nature (gravity, electro‑magnetism, the nuclear force and the weak force),

and that these forces act upon a finite number of particles that are pulled

this way and that by the summation of all forces acting upon each particle.

In laboratory experiments where the number of relevant forces can be confined

to only 1 or 2, motions are observed to be governed by a simple law: F = m•a, or "force equals mass times acceleration"

("acceleration" is the rate of change of "velocity vector"). It is easier to understand this law of nature by rewriting

it in the form: a = F/m, which states that

a particle's acceleration is proportional to the sum of forces acting on it

divided by the particle's mass. Mathematically, a and F are vectors, which is why these

symbols are written in "bold" typeface, and "m" is a scalar (no orientation

is involved); thus, the equation a = F/m keeps

track of the 3‑dimensional orientation of forces and accelerations. Since

forces can originate from many sources, they must be added together to yield

one net force.

At every instant

a particle is responding to just one net force. It responds by accelerating

in the direction of that force (which has a magnitude and direction). The particle's velocity vector changes

due to its acceleration. Since the time history

of a particle's velocity specifies where it goes, the particle's "behavior"

is completely determined by the forces acting upon it. This description is

called Newtonian physics, and it reigned supreme throughout the 19th

Century.

Quantum Physics

During the late

19th Century a disturbing number of laboratory measurements were

made that defied explanation using Newtonian physics. Radioactivity was a

puzzle, for it seemed that atoms of certain (radioactive) elements would

spontaneously, and at random, emit a particle. There was also the puzzle of

atoms absorbing and emitting light at only specific wavelengths, producing

a unique spectral pattern for each atomic element. Newtonian physics had no

way to accommodate these and other puzzling phenomena.

Quantum physics

was developed in response to these puzzling measurements, all of which were

related to mysterious phenomena inside the atom. The new physics expanded

upon the idea that everyday objects were constructed from electrons orbiting

a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons (now known to be constructed from

12 elementary building blocks of matter). It was

proposed that electrons could be thought of as a wave, with a wavelength

such that the only permitted orbital circumferences around a nucleus were

those with an integer number of wavelengths. Changes in an electron’s orbit

involved changes in energy, so if an electron moved to a higher energy orbit

(farther from the nucleus and larger in circumference) it must absorb energy

from somewhere (such as a photon of light) that had an energy corresponding

exactly to the difference in the electron’s energy in the two orbits – hence

the quantization of spectral absorption features for each atomic element.

As quantum

physics developed to explain more laboratory experiments related to the atom,

the theory became weirder and weirder. Quantum mechanics (QM) was developed

to deal with particles, and quantum field theory was developed to explain

radiation and its interaction with particles. Quantum physics has been

described as inherently probabilistic, or indeterminate, and has been characterized

as having so much "quantum weirdness" that our minds are intuitively unprepared

to comprehend it. Quantum physics “works” in the sense that it gives a better

account than any other theory for atomic scale physical phenomena. Contrary

to popular belief, it does not discredit Newtonian physics, which is still

valid for large scale phenomena; rather, it is more correct to say that

quantum physics supplements Newtonian physics. Almost

every physical situation can be easily identified as requiring one or the

other embodiment of physical law.

It now seems

that two of the aforementioned four forces can be "unified" (the weak and

the electromagnetic). One of the main goals of physics today is to create

a “unified” theory that incorporates all the explanatory power of the four

forces plus the weird but useful explanatory power of quantum physics.

One of the

most counter-intuitive properties of quantum physics is the notion that events

are not strictly determined but are only probable, and that particles are

not tiny things at a specific location but are probability functions in

3-dimensional space. When a particle moves the probability

function describing its location moves. In the laboratory it is impossible

to measure a particle’s position without changing its velocity; and it is

similarly impossible to measure a particle’s velocity without changing

its position. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle quantifies the partitioning

of position and velocity uncertainty.

Einstein believed,

but could not prove, that although we didn’t know of a way to measure a

particle’s position and velocity simultaneously with great accuracy, the

particle nevertheless has a well-defined position and velocity, and it interacts

with other particles as if this is so. His speculation was described as needing

a “basement level” of physical laws, which had not yet been discovered. With

a “basement level” of physical laws the apparent “unknowableness” of a particle’s

properties would be just that, apparent “unknowableness.”

The particle “knows” where it is located and how fast it is going, and in

what direction relative to the rest of the universe - even if humans can’t

know.

This “quantum

weirdness” is often cited to discredit the idea that events are “determined.”

But we cannot rule out the possibility that future physicists will discover

a basement level of physical law, and that this will restore Newtonian physics

as a complete theory for all size scales. The new Newtonian physics would

have the old Newtonian physics as a first approximation, valid for use with

the vast majority of physical phenomena dealt with on a daily basis.

Starting here I

will present only brief summaries of chapter sub-sections that have been

moved to Appendix A for this Second Edition of Genetic Enslavement.

Levels of

Physical Explanation

The matter

of “levels of physical explanation” must be dealt with for the reader who

is not prepared to accept the existence of a basement level of physical law.

In the physical

sciences it is common to treat a physical process at a “higher level” than

atoms interacting in accordance with the most basic level of physical law,

a = F/m and quantum physics. Instead, other

“laws” are constructed for everyday settings, either derived from the basic

level of laws or derived from experiment and deemed compatible with the basic

laws. One example should serve to illustrate this.

Consider the

atmosphere, which consists of an immense number of molecules. Any thought

of using a = F/m applied at the level of

molecules for the purpose of predicting the weather would be silly because

of its impracticality. There is no way to know the position and velocity

of all the molecules in the atmosphere at a given time for establishing the

"initial conditions" required for subsequent calculation using a = F/m. The meteorologist employs a “higher

level of physical explanation” by inventing “laws” that govern such aggregate

properties as "atmospheric pressure," “temperature,” and "wind speed."

In each case

the invented property and rules for using it can be derived from a = F/m, so these handy properties and rule

for usage are “emergent properties” of the basic level of physical laws.

Every atmospheric scientist would acknowledge that whenever a meteorologist

relies on a handy rule, such as “wind speed is proportional to pressure gradient,”

what is really occurring in the atmosphere is the unfolding of an immense

system of particles obeying a = F/m.

Just because

scientists find it useful to employ "emergent properties" does not mean

that the emergent properties exist; rather, they are no more than a useful

tool for dealing with a complex system. A "pressure gradient" doesn't exist

in nature; it exists only in the minds of humans. Model idealizations of

an atmosphere can be used to prove, using a = F/m, that the thing called a "pressure gradient" is associated

with wind. But these very proofs belie the existence of the concept, for they

"invent" the concept of a pressure gradient for use in a model that then

uses a = F/m. The handy meteorology rules,

and their "emergent property" tools, are fundamentally redundant to a = F/m.

The refinements

of modern physics do not detract from the central concept of materialism,

which is that everyday (large-scale) phenomena are the result of the mindless

interaction of a myriad of tiny particles in accordance with invariant

laws of physics. Reductionists acknowledge the importance of the many levels

for explaining complex phenomena, but they insist that all levels higher

than the basic level of physical explanation are fundamentally “unreal” and

superfluous, even though the higher level of explanation may be more “useful”

than a lower level of explanation.

Science embraces

what might be termed the "first law of reductionism," that whenever a phenomenon

can be explained by recourse to a more basic level of physical law, the “higher

level” explanation should only be used when it is drastically simpler to

use and unlikely to be misleading. Whenever a higher level of explanation

is used, there should be an acknowledgement that it is being used for convenience

only.

Living Systems

Reductionists

view living systems as subject to the same physical laws as non-living systems.

Therefore, the behavior of a living system is an emergent property of a

complex physical entity. A living thing is thus an automaton, or robot.

The thing we

call "mind" is an "emergent property" of an automaton’s brain. The brain consists

of electrons and protons, and these atomic particles obey the same physical

laws as inanimate electrons and protons.

Such things

as "thoughts, emotions and intentions" are mental constructions of the brain

that in everyday situations are more "useful" than the laws of physics for

the study of behavior. In spite of their usefulness, they are not actually

causing the movement of particles in the living organism, and they don't

exist at the most fundamental level of understanding.

Even “free will” must be shorn of its essential features, and recast as another

"emergent" product of real causes.

“Consciousness,”

like “free will,” is also an emergent property of automatons, just as the

"wind" is an emergent phenomenon of the atmosphere. I don’t object to the

use of “consciousness” for the same reason that I don’t object to the use

of “wind” when an atmospheric science problem is to be solved.

It has been argued

that the physicist exhibits "faith" in extending what is observably true

in simple settings to more complicated ones. This assertion of faith is true,

but the faith follows from the physicist's desire to invoke a minimum of

assumptions for any explanation.

Some Practical Considerations

Concerning Levels of Explanation

The brain evolved,

like every other organ, to enhance survival of the genes that encode for

its assembly. It should be no surprise, therefore, to find that it is an imperfect

instrument for comprehending reality. If it is more efficient to construct

brain circuits for dealing with the world using concepts such as spirits

and prayer, rather than reductionist physics, then the "forces of evolution"

can be expected to select genes that construct brain circuits that employ

these pragmatic but false concepts. Since no tasks pertaining to survival

requires the a = F/m

way of thinking, the brain will find this to be a difficult concept. It is

a triumph of physics to have discovered that a = F/m and quantum physics rule everything!

A naive person might

believe that the primitive person, viewing everything in terms of spirits,

is thinking at a higher level than the scientist. This would be a ludicrous

belief. A primitive is a lazy and unsophisticated thinker. He is totally

oblivious to reductionist "levels of thought." As I will describe later, he

uses a brain part that is incapable of thinking rationally: the right prefrontal

cortex. Human evolution's latest, and possibly most magnificent achievement,

is the left prefrontal cortex, which evolution uses to usurp

functions from the right prefrontal cortex when rational

thought is more appropriate (i.e., feasible). Too often contemporary

intellectuals will unthinkingly succumb to the pull of primitive thought,

as when someone proudly proclaims that they are “into metaphysics" (an oxymoron).

A fuller exposition

of this topic cannot be given without a background of material that will

be presented in later chapters. For now, I will merely state that mysticism

is a natural way of thought for primitive humans. It is "easier" for them

to invoke a "wind spirit" explanation than the reductionist ones, such as

a = F/m, or higher level derivative physical

concepts. They do this without realizing how many ad hoc

assumptions they are creating, which in turn require explanations, and this

matter is never acknowledged (as with invoking God as an explanation, without explaining "God"). Their thinking

may seem acceptable from the standpoint of a right prefrontal cortex (or

"efficient" from the perspective of the genes that merely want to create

a brain that facilitates the gene's "goal" of existing in the future), but

it is terribly misguided from the standpoint of the thinker endowed with

a functioning left prefrontal cortex, that demands rational explanations

with a minimum of assumptions. This unthinking proliferation of ad hoc assumptions bothers the reductionist, but it doesn't

bother the unsophisticated primitive.

Reductionism is

for the Few

H. G. Wells must

have understood the issues of this chapter. The reductionist paradigm was

an important part of intellectual thought during the 19th Century, and Wells

grasped it more surely than even many scientists today. Scientists, engineers

and inventors must have been held in high esteem during the second half of

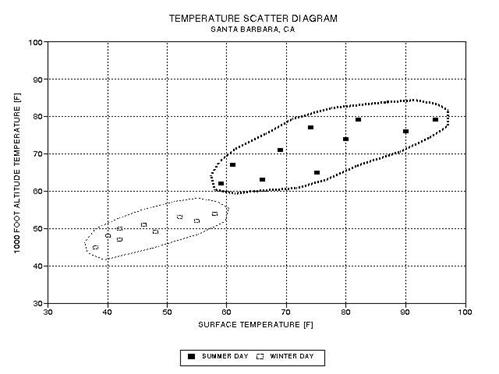

the 19th Century, and the first half of the 20th. The per capita number of

significant discoveries and innovations, as measured by Asimov's Chronology

of Science and Discovery (Asimov, informally distributed in the 1980s, formally

published 1994) peaked at about the middle of this period (actually, 1910

AD, as described in Chapter 15, and specifically Fig. 15.12).

Late in the 19th

Century, after Darwin’s evolution by

natural selection instead of divine guidance had time to register with intellectuals,

the idea of “humans as automatons” was part of the climate of opinion.

Thomas Huxley was intrigued by this idea, and Darwin humored him by

signing letters with a reference to it (Sagan and Druyan, 1992, pg. 70).

Reductionism requires that all living things be viewed as automatons, or robots

created by evolution. Yet none of today’s academics seem brave enough to

defend this idea.

Ernst Mach (1893)

deserves mention as an early champion of the idea that all branches of science

will eventually be viewed as unified. He was a continuing inspiration for

those who attempted to advance this perspective (Holton, 1993) throughout

the first half of the 20th Century. His was one of the most important

in a series of “flame-bearers” for keeping alive an idea that came out of

ancient Greece with the writings

of Democritus of Abdura (Sagan, 1980).

Reductionist ideas

were at least understood by literary people during the early 20th

Century. In 1931 novelist Theodore Dreiser, for example, wrote "I have pondered

and even demanded of cosmic energy to know Why.

But now I am told by the physicist as well as the biologist that there can

be no Why but only a How, since to know How disposes finally of any possible

Why." (Dreiser, 1931).

Sadly, we cannot

expect today's intellectuals to have the same profound understanding of the

nature of reality as was exhibited a couple generations ago by such writers

and social commentators as Wells and Dreiser. The quality of thought over

time, in a specific subject area, is not always progressive. As with civilizations,

there is a rise and fall in the sophistication of world views. Indeed, as

the 21st Century begins we are in the midst of a renewed interest in returning

to the comforts of primitive outlooks, as described in the next chapter.

─────────────────────────────────

CHAPTER

2

─────────────────────────────────

RESISTING THE BACKWARD

PULL

TOWARD OUR SPIRITUAL

HERITAGE

"O miserable minds of men! O blind hearts! In what darkness

of life, in what great dangers ye spend this little span of years! ... Life

is one long struggle in the dark." Lucretius, On the Nature of Things,

ca 60 BC.

"It does no harm to the mystery to

know a little about it. For far more marvelous is the truth than any artists

of the past imagined! Why do the poets of the present not speak of it? What

men are poets who can speak of Jupiter if he were like a man, but if he is

an immense spinning sphere of methane and ammonia must be silent?" Richard Feynman,

Lectures in Physics, Vol. 1, Addison Wesley, 1963.

The term "New Age"

is a misnomer, and an insult to better ages. It is a misnomer because it

is a regression to primitive ways of thinking, ways which should have remained

buried, yet which have resurfaced due to a mysterious mental pull toward

the primitive. This pull is unfortunately endemic to the flawed human mind.

"New Age" embraces the occult, a belief in angels, spirits, astrology, magic

and life after death. It is a return to the kinds of enslaving thoughts which

Lucretius urged his disciples to be rid of 2000 years ago.

The Primitive's

Reliance on Spirits

The environment

of our primitive ancestors, including both the physical and social aspects,

rewarded genes that constructed brains that could deal with the world, which

is profoundly different from stating that their environment rewarded brains

that could understand the world. As I argue in a later chapter, primitive

people did not employ the full powers of a modern left prefrontal cortex,

but instead relied upon a more primitive right cerebral cortex design for

both cerebral hemispheres. To the extent that "producing grandchildren" (a

convenient measure of genetic success) became more dependent upon mastery

of a world of human relationships instead of mastery of the natural world,

the architecture of the human brain evolved in ways that favored comprehending

the social world at the expense of the natural one.

The social arena

is less predictable than the natural one, so different mental abilities were

rewarded in an environment requiring social skills. When a brain that evolved

for the social setting addresses matters in the inanimate world, it should

not surprise us to find that such a brain employs "weird logic" in this

neglected realm. The primitive's vision of the world, being unguided by

rational thought, was filled with spirits that behaved like people. Primitive

people have gods for lightning, wind, rain, light, dark, and whatever seems

important to a primitive's precarious life. Thus, when the sun god loses

a conflict, according to this weird logic, it follows that there shall be

wind, rain and lightning.

Today’s common belief

systems provide evidence that for our ancestors the need to competently deal

with human affairs was more important to the evolving human genome than the

corresponding need to competently deal with the inanimate world. In high‑tech

modern Japan, for example, the

indigenous Shinto cult and religion remains popular. Shinto worship centers

on "a vast pantheon of spirits, or kami, mainly divinities personifying aspects

of the natural world, such as the sky, the earth, heavenly bodies, and storms.

Rites include prayers of thanksgiving; offerings of valuables..." (Encarta Encyclopedia, 2000). Even well‑educated Chinese

still believe in Feng Shui (the need to please spirits by a proper placement

of furniture, entrances, etc). American Indians, who crossed the Bering Strait 13,000 years ago,

brought with them a burdensome need for believing in spirits that demanded

ritual obedience. There seems to be an abundance of depressing examples from

every culture.

The Dyads of Primitive

Thinking

Dyads abound in

primitive thinking. Night and day, good and bad, friend and foe, birth and

death ‑ they all contribute to a "yin and yang world." It is not surprising

that when primitive men floundered to explain the world, they relied upon

a dyadic competition. Thus, night and day are engaged in a daily struggle,

literally; and at sunrise the "day" has become victorious over "night," and

so on. But it gets complicated, for during winter the stronger competitor

is night, whose exhaustion gives day the upper hand during summer.

Conflict permeates

a primitive's thinking, because conflicts between tribes define primitive

life. Nevertheless, men battle upon a stage set by even stronger forces than

themselves. The weather is overwhelmingly strong, as is the ocean, the occasional

earthquake, tsunami and volcano. There must be gods in heaven who unleash

the thunderstorm and lightning, that punishes

and rewards men. Since powerful men can be appeased, or slightly influenced,

so might the gods. Man's quest for control over his fate led him in false

directions, for gods cannot be appeased when they don't exist.

We should laud the

primitive's urge to explain, even though it seems to be only weakly motivated

by an urge to understand. The human claim for nobility rests upon this urge.

But let us also not be mistaken about the explanations created by primitive

men: Primitives have been stupendously wrong in almost every instance!

Their explanations

were wrong because they arose from a primitive right brain. Only recently,

with the ascendance of the aforementioned, fast‑evolving left brain, with

its logical mode of thought and lack of traditional "wisdom," has it been

possible to conjure up correct explanations. But, so strong is the irrepressible

right brain that even many contemporary "intellectuals" still believe that

primitive explanations contain some profound and subtle wisdom that makes

it "just as valid."

Thinking men of

every age seem to have sensed a pull toward primitive thinking, and worse,

toward primitive behaving. The decay of civilization has been an ever‑present

concern for those who live in a civilized state. This concern was expressed

by ancient Greek philosophers, just as it is in today's world.

We know that the

civilized state is not secure, because we sense the presence of that insistent

and primitive right brain. To use the primitive's own metaphor, we are engaged

in a struggle between good and bad, between light and dark, and it is now

"late afternoon." Some of us who worry about the

approach of evening, and a long night, admonish our contemporaries to resist

the "primitive pull," to stay the course that brought us to this glorious

noon, atop the highest

mountain, by keeping the new faith as it struggles with the old. It has

become a battle between the two titans of human history:

the two brain halves!

The Modern's "Spiritual

Cleansing"

The primitive way